Buttons pop off your expensive new shirt after only a month of use. A piece of hull flies off an airplane in mid air, leaving a gaping hole next to passengers. Navy ships crash due to unforced errors; people die. The hospital nurse forgets to bring your grandmother her medicine at the scheduled time: "Hah! silly me..."

It's easy to feel like you are living through an Ayn Rand novel sometimes. "Why don't things work like they used to?"

Many people believe we are seeing the early signs of a "competence crisis". Perhaps "diversity hires" are to blame? Another way to put it is, the leaders of companies, institutions, and first world countries seem, somehow, to have lost their edge. They appear to be demoralized.

"Demoralize" is a concept coined during the French Revolution. It means to lower your enemy's morale, their courage and will to fight. If you can get the representatives of the ancien régime to lose their morale, it's easy to win the Revolution. The aristocrats once seemed so formidable didn't they? But a demoralized man doesn't have access to his full powers; with a little shove, he tips over like a bowling pin.

"Morale" comes from the Latin moralis, "pertaining to mores (="customary habits" or "character")". Originally, therefore, the concept had a wider semantic field. But "morale" today indicates the single virtue which, in classical theory, is the foundation of the rest: courage. An individual or an army with "good morale" is one that fires on all its cylinders. If morale is present, the rest of the virtues are likely to join too.

This leads us to an important lesson.

True competence, that is, executing well on hard things, requires morale. In the past, society's paragons of competence were generals and statesmen. The military historian Martin Van Creveld has called Napoleon "the most competent human being who ever lived." So, what did Napoleon do for his own morale? Over some 20 years of campaigning, he took with him Plutarch's Life of Caesar and often reread it on the eve of battle.

If we want to move into positions that require our utmost competence, we have to moralize ourselves. Not like a Sunday schoolmarm tut-tutting us with platitudes, but like Napoleon doing his pregame psych-up. Did Napoleon have anything more to learn about logistics, tactics, or battle strategy from reading Plutarch's biography of Caesar for the 37th time? No, rather, he used the story of Caesar to remind himself of who he was, by recalling to mind a man whom he always aspired to be like.

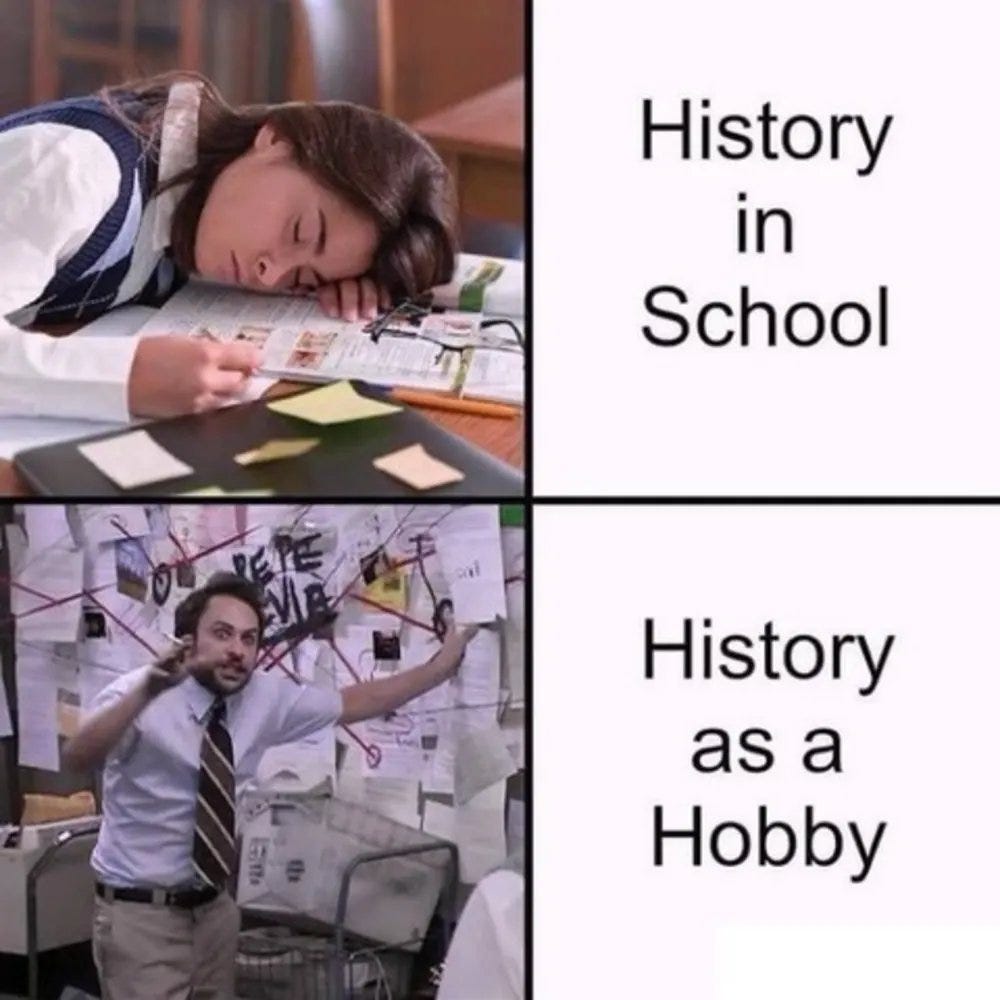

Modern education usually beats out of us any habits like these. History, we are told, is about considering both sides of a problem, it's about gathering evidence and evaluating it objectively, or (worse), it's about trudging through some sad tale of oppression through the centuries. At best, the typical received opinion says history is about presenting all the "facts."

History can be many things, and facts are important. But if history can't fortify us on the eve of battle, it has failed at its most important purpose - to inspire action in the present. When taking the "moral" approach to reading history, according to Nietzsche, we should be willing even to "do violence" to the facts in our own minds -- as long as this imaginative act brings out the best forces from within us. (He called it "monumental history")

When I started teaching as a young academic, a superior once urged me to avoid indulging in too much storytelling - especially the "inspiring" kind. In pedagogy seminars, professors encouraged me to design new curricula that sidestepped the less "relatable" great authors like Sophocles and Plutarch, or at least balanced them out with writings from "subaltern," lesser known, "non elite" writers, or perhaps "critical scholarship," or data from archaeological studies of "material culture."

Under the guiding wisdom, if an ancient source - or, for that matter, scholars of the previous generation - identified a particular individual (say, Lycurgus of Sparta, or Caesar) as a unique agent responsible for something great, such as the foundation of a city or nation, or a military victory, I was supposed to smirk and look elsewhere to find "the real causes" - economic patterns, geography, ideology, exploitation, or - best of all - climate change.

I have always been naturally curious, and so I preferred to give alternative perspectives the benefit of the doubt. But there was one place I knew for certain that I should never, under any circumstances, let my curiosity go - if, that is, I cared at all about my career and being taken seriously as a scholar. I could never let myself engage in "hero worship." The great and the good, men like Cicero, Cato, Plato and Thucydides, were all to be looked at with a mix of sarcasm, skepticism, and condescension. To honor such heroes and hold them up as models for emulation was to be uncritical.

If you subject a large group of people, for example an entire generation of young students, only to these anti-hero approaches, you can demoralize an whole society. If history doesn't give us energy, but rather drains it from us, we may be witnessing the consequences of a deliberate, industrial-scale demoralization.

(Thanks

for this meme)How can we make sure we don't allow the cycle of demoralization to continue? We can start by studying the great deeds of all the incredible figures that we were subtly trained to ignore because they weren't "on the test." And we can make sure the people who will build and run the complex, high stakes technologies of the future - our children, especially - get "moralized" in the right way, the ancient way.

For this, the Cost of Glory podcast is at your service.

Stay Ancient,

Alex

PS:

I posted a deep dive on some of these issues with my buddy

of Young Heretics Podcast this past week.Also, check out my friend Ben Wilson’s excellent new podcast series on Napoleon.

I feel the passion in this essay. A strong passion communicated softly. Well done Alex.

Now I will save this post in my head as a companion piece to C.S. Lewis's Abolition of Man:

"In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful."

Great post! Reminds me of the last few lines of the poem:

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.