I probably should have done a “year in review” post. Maybe next time. But I do have some good news to share: in 2024 Cost of Glory will be getting bigger, better, faster, etc. More details coming soon. I am grateful for all of your support and thoughtful attention over this journey!

Plutarch was a pagan who catalogued the exploits of some of history's most warlike, ambitious, and ruthless men. Yet so many die hard Plutarch fans I meet are Christians. Isn't Christianity a religion that preaches peace, humility, and consideration for others? What explains the tension?

It's not a new phenomenon. In the 11th century, the Byzantine poet scholar John Mauropus lifted up a prayer for two pagans:

If any of the heathen, O my Christ,

You might from condemnation deign to save,

Then rescue Plato please, and Plutarch too:

For likewise in their doctrine and in morals,

Both men to your commandments are allied,

And true, though neither knew you to be God,

Yet, all that's needed is your holy Grace,

Which saves the rest of our unworthy lot.

Εἴπερ τινὰς βούλοιο τῶν ἀλλοτρίων

τῆς σῆς ἀπειλῆς ἐξελέσθαι, Χριστέ μου,

Πλάτωνα καὶ Πλούταρχον ἐξέλοιό μοι·

ἄμφω γὰρ εἰσὶ καὶ λόγον καὶ τὸν τρόπον

τοῖς σοῖς νόμοις ἔγγιστα προσπεφυκότες.

εἰ δ’ ἠγνόησαν ὡς θεὸς σὺ τῶν ὅλων,

ἐνταῦθα τῆς σῆς χρηστότητος δεῖ μόνον,

δι’ ἣν ἅπαντας δωρεὰν σῴζειν θέλεις.

By the time those lines were written, Christian leaders and intellectuals had been reading Plutarch for nearly a millennium. Church fathers like Clement of Alexandria (2nd century), Basil "The Great" of Caesarea (4th century) and Gregory "The Theologian" of Nazianzus (4th century) quote him often. Plutarch was extremely popular in the Renaissance. In the pious age of the American Founders, his biography collection, the Parallel Lives, was the second most popular ancient text after the Bible. The Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather praised "the incomparable Plutarch" and made wide use of him.

So again, why have devout Christians held Plutarch in such high regard through the ages?

Here are three reasons I've come up with, in increasing order of their timeliness for today.

1) Plutarch helps Christians satisfy their peculiar devotion to a specific historical period.

Jesus Christ was born in the Roman province of Judea, during the reign of Augustus Caesar. The New Testament assumes we know what this all meant. But you might wonder, for example, why were the Romans in this foreign land in the first place?

We can turn to Plutarch's Life of Pompey for an answer: the Roman general Pompeius Magnus exploited a civil war in Judea when he was in the neighborhood, ostensibly warring against King Mithridates of Pontus, but in reality exploiting the opportunity to conquer much of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Who is Augustus Caesar? Plutarch again: before he changed his name to Augustus, Octavian battled Mark Antony for control of Rome, and after victory became its first emperor. The struggle is narrated in Plutarch's Life of Antony. And why was the New Testament written in Greek, not Hebrew, Aramaic, or Latin? Short answer: Because the Macedonian Greek Alexander conquered the near East, as told in Plutarch's Life of Alexander.

The biographies of Plutarch cover almost all of the most important events and characters of the ancient Greco-Roman world leading up to the advent of Christianity, as I've illustrated here.

Most importantly, Plutarch teaches you this all in the most entertaining and memorable form: dramatic, vivid biographies of the leading figures. As Ralph Waldo Emerson observed, "[Plutarch] disowns any attempt to rival [the Greek historian] Thucydides; but I suppose he has a hundred readers where Thucydides finds one, and Thucydides must often thank Plutarch for that one."

Reading Thucydides is a little like slonking raw eggs: Undeniably, it fortifies you, but it makes some get woozy and throw up the first time. Plutarch, however, makes the medicine go down smoothly. He helps you build a mental framework of memorable guideposts that will help you to put other great ancient works into context, making them eventually more enjoyable too.

This general knowledge of antiquity Plutarch offers also helps us better understand other great, later classics of Christendom like Dante and Shakespeare, who often used Plutarch himself as their primary source (E.g. Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, and Coriolanus).

2) Biography is uniquely important for Christians

If all mankind needed for salvation was words, God could have just sent more Prophets. Instead, the task required deeds as well - thus He personally assumed human nature, and showed humans the Way.

Humanity's response was to produce Greek biographies (the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John).

Not every culture produces biographies. The Romans of the Republic didn't. But as the Greek philosophers who invented the genre in the 4th century BC saw, biography captures the principles of success and happiness in a uniquely learnable form. If you want to promote a certain lifestyle, biography is a great tool. From the early Christian biographies like Athanasius' Life of Antony and the brief portraits in the Lives of the Desert Fathers, to the many biographical sketches of early American Puritans in Cotton Mather's Magnalia Christi Americana, Christians have used biography as an entertaining way to spread their message for centuries.

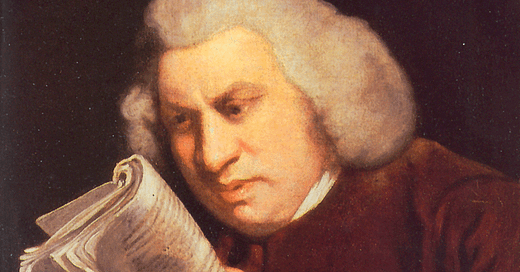

It's no surprise that in doing so, Christian writers looking for a literary model have turned to "the prince of ancient biographers," as Boswell dubbed Plutarch in the preface to his Life of Samuel Johnson.

3) Hard Times Require Courage

"The first of all qualities," wrote Marshal Maurice de Saxe in his Memoirs Concerning the Art of War, "is courage. Without this, the others are of little value, since they cannot be used." Whatever vices Plutarch's often flawed heroes might have suffered from, they all possessed cartloads of courage.

In classical Christian doctrine, courage - andreia, literally "manliness" in Greek - is the foundation of the other virtues. It is all over the New Testament, as in Paul's exhortation to the Corinthian Christians to "man up" (andrizesthe, 1 Cor 16:13).

Courage lays a broad foundation - and one that the secular and spiritual realms share. Hence the NT writers' frequent use of military and athletic metaphors, such as Paul's exhortation to Timothy to act like a "good soldier of Jesus Christ" (2 Tim 2:3).

Courage, as Plato observed in the Republic, is a virtue we increase by training the parts of the psyche that are less discursive and more instinctive. This includes listening to stories of brave men doing brave things: such narratives have a powerful moral effect, especially on the youth, and operate to some extent subconsciously to increase a man's store of courage. Plato's conclusion is that anyone who wants to build a healthy and courageous state or personal character needs to control the story inputs - and the most important criterion is courage.

This in part explains the popularity of Plutarch's heroes around the heady state building era of the American Revolution. From Epaminondas' defiance of the Spartan supremacy and Pelopidas' incredible coup at Thebes, to Fabius Maximus wearing down Hannibal, and Cato's defiance of Julius Caesar, Plutarch's Parallel Lives showcase courage in its utmost extremes. It's not least for this quality that George Bernard Shaw called the Parallel Lives a "Revolutionist's handbook."

Thus whenever Christians have faced intimidating challenges in their personal or political lives, they have turned to Plutarch. As St. Basil of Caesarea wrote to a young mentee of his, "the renowned deeds of the men of old either are preserved for us by tradition, or are cherished in the pages of poet or historian, we must not fail to profit by them." He went on to recount a story from Plutarch's Life of Pericles to drive home his point.

Though Basil wouldn't place Plutarch on the same level as the Holy Scriptures, nevertheless, like other Christians through the centuries, he saw Plutarch as an especially valuable moral fortification for men operating in the secular realm.

Whatever your religious commitment or lack thereof, Plutarch can be your companion in courage. It's also why I make the Cost of Glory podcast - to help you increase your input rate of these timeless and fortifying stories.

Stay Ancient,

Alex

PS. I'd love to meet you in Rome this summer for the 2024 Cost of Glory Men's Leadership Retreat. Our focus is on applying the lessons of Plutarch's great leaders and speakers in order to become better speakers ourselves. Find out more at costofglory.com/retreat.

I happened to read Thucydides first, and found that I got more out of many Plutarch biographies by virtue of bringing some context for many of the figures to the reading of their biographies.

I highly recommend the Landmark Thucydides. I didn't find this a "slog" by any means. It is still one of my favorites.