Amphibious Assault — De Bello Gallico - Part 4

Part 4 of an 8 part series on Caesar's Gallic Wars...

Caesar crosses two major bodies of water (and he hasn’t even gotten to the Rubicon yet), in part 4 of our series on Caesar’s masterwork of psychology, strategy, and propaganda: On the Gallic War (De Bello Gallico).

This is a world-history making story (the conquest of what’s now modern France), told by a world-history making storyteller.

Caesar entered Gaul as a mere politician. He returned 9 years later as a conqueror - and an enemy of the state. He tells how it all happened with his own pen.

In this episode:

The Suebi and their strange ways

Caesar builds a bridge

Caesar’s first landing in Britain

This episode is sponsored by our very generous sponsor, Dr. Richard Johnson, an avid Cost of Glory listener. Thank you Richard! If you’re interested in sponsoring an episode, feel free to get in touch, any support is highly appreciated as it helps me create more high quality work for my dedicated audience.

You can listen to the episode here:

Stay Ancient,

Alex

Announcement: I’d love to see you in Ecuador next month (August 22-25) for an amazing event I’m organizing with some friends. More info Here at this post below:

How Empires are Built

"Plato’s Academy, *by far* the most successful philosophy school in antiquity, was not primarily a set of ideas, but a self-perpetuating, decentralized network, united by a common vision." I’m co-organizing and speaking at an event August 22-25 in Ecuador. I’d love to meet you there - or some other time.

Transcript

In the following winter, in the year in which Gnaeus Pompeius and Marcus Crassus were consuls, the Usipetes from Germany, and likewise the Tencteri, crossed the Rhine River in huge numbers, not far from the sea into which it flows…

A single sentence opening Caesar's book 4 of De Bello Gallico ... a single sentence, containing both Caesar's greatest problem this year, and its solution. What's the problem? That German hordes are crossing the Rhine? No, no.

That's the solution, you see.

The problem is, it's the year 55 BC, and the two most powerful men in Rome are the year's two consuls—once again (as they did long ago in the year 70)—Pompey and Crassus, Rome's greatest men and arch rivals.

Well, Caesar has brought them to the compromising table once more, and brokered a deal.

How do you make sure your two senior colleagues - and the rest of Rome - won't forget about you while you're off fighting obscure wars in faraway lands?

Well, what about a grand expedition to smash through a border that no Roman general has ever crossed? What about... two such expeditions? Something for his soldiers and staff officers to write home about?

I'm Alex Petkas, you are listening to the Cost of Glory where it is our mission to retell the lives of the great Greek and Roman Heroes, following the lead of the great philosopher biographer Plutarch... and... to take the occasional detour to zoom in on the writings, and the peculiar adventures, of certain of those heroes, as we are today. This is part 4 of 8 of Caesar's Gallic Wars.

The Cost of Glory is produced in collaboration with Infinite Media.

And also, big thanks to Dr. Richard Johnson for sponsoring this episode.

In this show... new, strange peoples, and their strange ways, and how Caesar sizes up their strengths and weaknesses, in order to get the upper hand.

Let's get to it.

The Germans cross the Rhine

So the beginning of the book, which we just read, you've got two large German nations, the Usipetes, and the Tencteri, crossing the Rhine, from Germany, in the east, into Gaul to the west. And this, of course, offers a very interesting opportunity for Caesar.

Caesar recognizes the Rhine river as essentially the natural border between Germany and Gaul, it's a bit of an oversimplification but it's more or less fair. Now, the Rhine rises in the Alps, it bends West at Lake Constance, and then bends North... that bend from east-west to south-north actually forms the border of the southwest corner of Germany today; from there the Rhine heads generally North for maybe two hundred miles, before bending off to the northwest around Frankfurt, and on further northwest through Cologne, and it winds up emptying into the ocean through what's now the Netherlands.

And it was somewhere in that north-western lowland, downstream section of the Rhine that the Tencteri and Usipetes decided to try their hand at a migration into Gaul.

Caesar explains though that they had good reasons for doing this:

The reason for their crossing was that for many years they had been harassed by the Suebi, who continually pressured them with armed attacks and prevented them from farming their fields.

Who are the Suebi?

And he's going to tell us more about these Suebi, who incidentally give their name a region of modern Germany called Swabia.

Here's Caesar on the Suebi:

The Suebi are by far the largest and the most warlike nation among the Germans. It is said that they have a hundred cantons, from each of which they draw one thousand armed men yearly for the purpose of war outside their borders. The remainder, who have stayed at home, support themselves and the absent warriors; and again, in turn, are under arms the following year, while the others remain at home…

So they've got, by this logic, 200,000 fighting men, each half of which takes its turn year by year to go out and do battle full time in the campaign season.

…By this means neither husbandry nor the theory and practice of war is interrupted. They have no private or separate holding of land, nor are they allowed to abide longer than a year in one place for their habitation. They make not much use of grain for food, but chiefly of milk and of cattle, and are much engaged in hunting; and this, owing to the nature of the food, the regular exercise, and the freedom of life — for from boyhood up they are not schooled in a sense of duty or discipline, and do nothing whatsoever against their wish — nurses their strength and makes men of immense bodily stature. Moreover, they have regularly trained themselves to wear nothing, even in the coldest localities, except skins, the scantiness of which leaves a great part of the body bare, and they bathe in the rivers. They give access to traders rather to secure purchasers for what they have captured in war than to satisfy any craving for imports.

They sound a little bit like your typical roving pastoral war band types, don't they? Milk and flocks, disdain for agriculture, love of war and plunder... freedom above all. You can see why 18th and 19th century European ethnologists pored over passages like this one to trace the roots of the more glorious days of Germanic peoples...

Caesar is probably drawing to some extent on hearsay from the occasional merchant, and there are some stereotypes built in here, but Tacitus confirms much of this picture, if you read his short, excellent work the Germania, written about 150 years later, based on 150 more years of Roman experience fighting against and alongside the Germans.

Tacitus notes for instance that,

When not engaged in warfare, they spend some little time in hunting, but more in idling, devoting themselves to sleep and gluttony. All the brave and fierce warriors do nothing at all; the care of the house, hearth, and fields is left to women, old men, and the frailest of the family, while they themselves laze about. It is a remarkable inconsistency in their nature that [the Germans] love indolence as much as they hate peace

—Tacitus, Germania, 15

Caesar here is going to get a little bit more specific here about the war tactics of the people he's about to engage with here. Here's Caesar on the Germans in general:

And, in fact, the Germans do not import for their use draught-horses, in which the Gauls take the keenest delight, procuring them at great expense; but they take their own home-bred horses, deformed and ugly as they are, and by regular exercising they render them capable of the utmost exertion. In cavalry combats they often leap from their horses and fight on foot, having trained their horses to remain in the same spot, and retiring rapidly upon them at need; and their tradition regards nothing as more disgraceful or more indolent than the use of saddles. And so, however few in number, they dare approach any party, however large, of saddle-horsemen. They suffer no importation of wine whatever, believing that men are thereby rendered soft and womanish for the endurance of hardship.

So yes, they don't want anything to "take the edge off" so to speak... they thrive on maintaining that edge. Tacitus by the way also notes that the Tencteri, one of the tribes Caesar is talking about here, were especially noted among the Germans for their horsemanship.

But let's finish Caesar's field ready ethnography here, he's going to tell us more specifically on the Suebi:

As a nation, they count it the highest praise to have the land on their borders untenanted over as wide a tract as may be [in other words, they don't allow anyone, themselves or others, to cultivate land around their borders], for this signifies, they think, that a great number of states cannot withstand their force. Thus it is said that on one side for about six hundred miles from the territory of the Suebi the land is untenanted.

So these Suebi are a massive nation, really a broader coalition of different nations... deep in German territory, far beyond the Rhine... but the situation that Caesar is currently dealing with is that the Suebi have chased the Usipetes and the Tencteri out of their homelands, and so these latter people, after being driven out by the Suebi, they decide to cross the Rhine and take the land from these softer Gauls.

And Caesar claims that they brought a whole mass of people, two whole nations across the Rhine, 430,000 in total (of which maybe 100k would have been fighting men).

The way they did it was by playing a trick on this one Gallic tribe that sort of straddles the Rhine, the Menapii. They started by making a sort of testing attack on the Menapii at the Rhine, they were fought back, then they retreated three days back from the Rhine, the Menapii relaxed, and then the Germans made a blitzkrieg and caught the Menapii off guard and overwhelmed them, so then they took the Menapii's boats and crossed the Rhine.

And now, we have a situation that clearly needs Caesar's attention.

Caesar’s response to the crossing

Now, Caesar ends up catching a lot of heat in the Senate back in Rome for what he decided to do here, so he spends some care describing exactly what happens next.

So, you've got the position of the new German arrivals laid out now, well now here's Caesar's perspective:

Caesar was informed of these events; and fearing the fickleness of the Gauls, because they are capricious in forming designs and intent for the most part on change, he considered that no trust should be placed in them. [This next part is funny, but it gives you a sense of what it's like to live in one of these Gallic towns near the border:] It is indeed a regular habit of the Gauls to compel travellers to halt, even against their will, and to ascertain what each of them may have heard or learnt upon every subject; and in the towns the common folk surround traders, compelling them to declare from what districts they come and what they have learnt there. Such stories and hearsay often induce them to form plans upon vital questions of which they must forthwith repent; for they are the slaves of uncertain rumours, and most men reply to them in fictions made to their taste."

So Caesar goes on to explain, essentially, if he lets these Germans come in and stay, unchecked, this creates a new wild card politically and militarily, because of the fickleness of the Gauls.

You might remember the Ariovistus incident from book 1, Ariovistus and the Germans get invited across by the Sequani because the Sequani think they can use these Germans as allies, as leverage against their neighbors. And then the Germans end up dominating and terrorizing them and everyone else; so here now with the Usipetes and Tencteri, you can see how some weaker Gallic tribe might get the idea, that these Germans can help us overthrow the Romans, or maybe some haughty Gallic allies Caesar has put at the top of the local pyramid...

And you know, that's a pretty fair assessment of the danger here. Caesar doesn't want to have a bigger war on his hands later.

So he races from Cisalpine Gaul, joins up with his army, and he moves 8 legions (!) into a position near the Rhine.

Once he gets there, the Germans get nervous and they send some emissaries to treat with Caesar:

When he was a few days' march away deputies arrived from [the Usipetes and Tencteri], whose address was to the following effect: [here we have some typical Germanic free speaking:] 'The Germans would not take the first step in making war on the Roman people, however, if provoked, they would not refuse the conflict of arms, for it was the ancestral custom of the Germans to resist anyone who made war upon them, and not to beg off. They declared, however, that they had come against their will, being driven out of their homes: if the Romans were interested in the goodwill of the Germans, they might find their friendship to be useful. Let the Romans either grant them lands, or allow them to hold the lands which their arms had acquired. They themselves yielded to the Suebi alone, to whom even the immortal gods could not be equal; on earth at any rate there was no one else whom the Suebi could not conquer.’

Caesar's response is pretty stern. He says, sorry, you can't be friends with the Romans as long as you remain in Gaul.

This is a pretty bold claim on Caesar's part, isn't it? He's basically saying, all of Gaul is my business now ... what a change from just a couple of years ago. And these regions that he’s in are still very much NOT a proper Roman province...

And he continues with a little jab:

It is not just that men who have not been able to defend their own territories should seize those of others; on the other hand, there is no land in Gaul which can be granted without injustice, especially to so numerous a host.

He does offer them, however, that he can help them try to make a deal with the Ubii, another Gallic tribe which happens to live on the German side of the Rhine... and who also have struck up some kind of an alliance with Caesar, and they have their own complaints against the Suebi... Caesar's even got some of the leaders of the Ubii in his camp.

So, honestly, it's not a very appealing offer to these ambassadors probably, once you have crossed 400,000 people over a big river, won some battles, conquered some territory, to now have to go tell your followers, OK, change of plans, we're going back across...

But hey, it's an offer at least.

The Germans say: ‘ok, we'll take this back to our leaders, we'll be back in 3 days’... but they ask, ‘please, can you not advance your army any further towards our camps?’ Caesar says sorry, I can't guarantee that.

And he says, he believed they were just buying time to wait for their cavalry to return from a big raid (he knew they were raiding another Gallic tribe nearby).

So he keeps marching, and once he's only 12 miles away from the German camp, the ambassadors come back, 3 days have passed, and they plead again, please, just don't advance any further, we need more time to work something out... He says no, but he does grant another reasonable request, (this is key) they ask him not to engage in any fighting until they've had a chance to go make their case with the Ubii, the people across the Rhine Caesar sent them to, to go ask for their hospitality.

So, the Romans have committed to a cease fire, and so have the Germans. This is the background of the crisis situation that happens next.

So... while Caesar's got his cavalry patrolling the German camps, not expecting any funny business... suddenly 800 German cavalry attack them.

The First Deadly Skirmish

The Romans have 5,000 cavalry, but they're all spread out on various patrols, and so, with their ugly little horses, the Germans manage to put all the Romans' cavalry to flight (remember these would be Gallic allied auxiliaries, and so the numbers you're about to hear are not huge but, keep in mind that these would have been the flower of the nobility of the allied Gauls):

When our men turned to resist, the enemy, according to their custom [we saw him describing this tactic earlier], they dismounted, and, by stabbing our horses and bringing down many of our troopers to the ground, they put the rest to rout, and indeed drove them in such panic that they did not desist from flight until they were come in sight of our column. In that engagement were slain seventy-four of our cavalry, and [he's going to zoom in on one particular example here] among them the gallant Piso of Aquitania, the scion of a most distinguished line, whose grandfather had held the sovereignty in his own state, and had been saluted as Friend by the Roman Senate. Piso went to the assistance of his brother, who had been cut off by the enemy, and rescued him from danger, but was thrown himself, his horse having been wounded. He resisted most gallantly as long as he could; then he was surrounded, and fell after receiving many wounds. His brother, who had escaped from the fight, saw him fall from a distance; then spurred his horse, flung himself upon the enemy, and was himself slain too.

So, that's a tragic end for this brave young man Piso of Aquitania and his brother... but I think Caesar includes that to heighten, for his readers back in Rome, the emotional power of this defeat... which was relatively minor strategically, and in terms of the numbers lost... but Caesar still treats it as a grave outrage, because it happened in the context of a truce - and personalizing the story like that with young Piso really brings the point home.

And it's going to justify what he does next.

Now, Caesar happened to request at the earlier meeting of the German ambassadors that they return to him on the following day with as large a group of ambassadors as possible, so he could hear their demands (this was before the surprise breaking of the truce with that attack).

Which strikes me as an odd request to make...

But the Germans do it, they return indeed with a big delegation, not in the circumstances they had been expecting the day before - because now they are pleading with him trying to explain their sin, “ah, Caesar, this was all a misunderstanding!” (and, you know, it's very plausible, considering the warlike nature of these ornery people, that the leaders simply didn't have a whole lot of discipline over their fighting men, and it really was a sort of accident).

But Caesar claims, no, it’s treachery, these guys are lying through their teeth.

So he proceeds next with extreme prejudice - he seizes these ambassadors (as large a group as possible, remember), and then, he sends his army full strength, full assault mode, against the now rather leaderless Tencteri and Usipetes at their camp.

He notes along the way, once again, as a major reason for his swift action, the fickleness of the Gauls - in other words, word spreads quickly through the Gallic towns, as he's noted, defeats get exaggerated, stories get told... and he doesn't want word getting out that he's soft, or that the Romans have met their match, or anything like that.

He's Caesar, he's got a reputation to uphold.

And so he operates at full Julius Caesar speed, in this sudden attack on these Germans. The result was... such as to make your stomach turn:

The eight-mile march was so speedily accomplished that Caesar reached the enemy's camp before the Germans could have any inkling of what was toward. They were struck with sudden panic by everything — by the rapidity of our approach, the absence of their own chiefs; and, as no time was given them to think, or to take up arms, they were too much taken aback to decide which was best — to lead their forces against the enemy, to defend the camp, or to seek safety by flight. When their alarm was betrayed by the uproar and bustle, our troops, stung by the treachery of the day before, burst into the camp. In the camp those who were able speedily to take up arms resisted the Romans for a while, and fought among the carts and baggage-wagons; the remainder, a crowd of women and children (for the Germans had left home and crossed the Rhine with all their belongings), began to flee in all directions, and Caesar dispatched the cavalry in pursuit.

This battle... to put it briefly, decimated and scattered the nations of the Usipetes and the Tencteri.

Outrage at the Homefront

And Caesar was probably thinking pretty highly of his accomplishments at this point, ugly as the business was, but here's Plutarch on what happened on the home front:

(This is from the Life of Cato the Younger, who is Caesar's most determined political enemy):

After Caesar had fallen upon warlike nations and at great hazards conquered them, and when it was believed that he had attacked the Germans even during a truce and slain three hundred thousand of them, there was a general demand at Rome that the people should offer sacrifices of good tidings, but Cato urged them to surrender Caesar to those whom he had wronged, and not to turn upon themselves, or allow to fall upon their city, the pollution of his crime.

Now, Cato and Caesar's other enemies could point out that, well, here you have a case where a man who only the previous campaign season, against the Veneti, took the Gauls' seizure of ambassadors to be just cause for waging war, now he's seizing ambassadors of his enemy (who, by definition, come under the banner of a truce, right?).

Caesar would of course respond, well look at the facts, see, the Germans broke the truce first, by attacking our cavalry.

And yet... a cynic might wonder: Why would Caesar make that odd request of the Germans the day before, come tomorrow with as many of your leaders as you can gather? Is it possible that he knew there was going to be a scuffle between his cavalry and theirs? is it possible that... someone among his cavalry had been given instructions to provoke the Germans into an engagement? All it might take to stir up a proud and volatile barbarian people would be a carefully thrown spear... to lure them into attacking the Roman cavalry, giving Caesar the perfect justification for seizing ambassadors and then winning an overwhelming victory against a leaderless mob of people…

Is it possible that someone leaked such a cynical plot to Cato, who therefore had better information than we are receiving from Caesar's commentaries?

Well... that's a little far fetched surely.

And anyway, you don't even have to go down any conspiracy theory rabbit holes to appreciate how ruthless and calculating Caesar could be, when he judged he needed to be.

He may genuinely have thought, all along, even if the cavalry attack was a mere misunderstanding, that on the whole the Germans were still basically just buying time, and they had no intention of crossing back over the Rhine (which is very plausible). So he decided, he would fight them on his own terms. And thus, he seized the ambassadors and attacked without warning.

Thankfully, for Caesar, nothing at all came from Cato's railing against him in the Senate.

In fact, at some point during this year (perhaps before this incident) Caesar would have gotten the news that, all according to plan, a friendly tribune of the plebs, Trebonius, had proposed a law extending Caesar's command in Gaul another 5 years, and his friends Crassus and Pompey, as consuls, had made sure that the necessary voting blocks were assembled, and the unnecessary voters (the nay sayers that is) were strongly encouraged to keep clear of the ballots on the scheduled day.

But all those matters though are best left for the biography episodes.

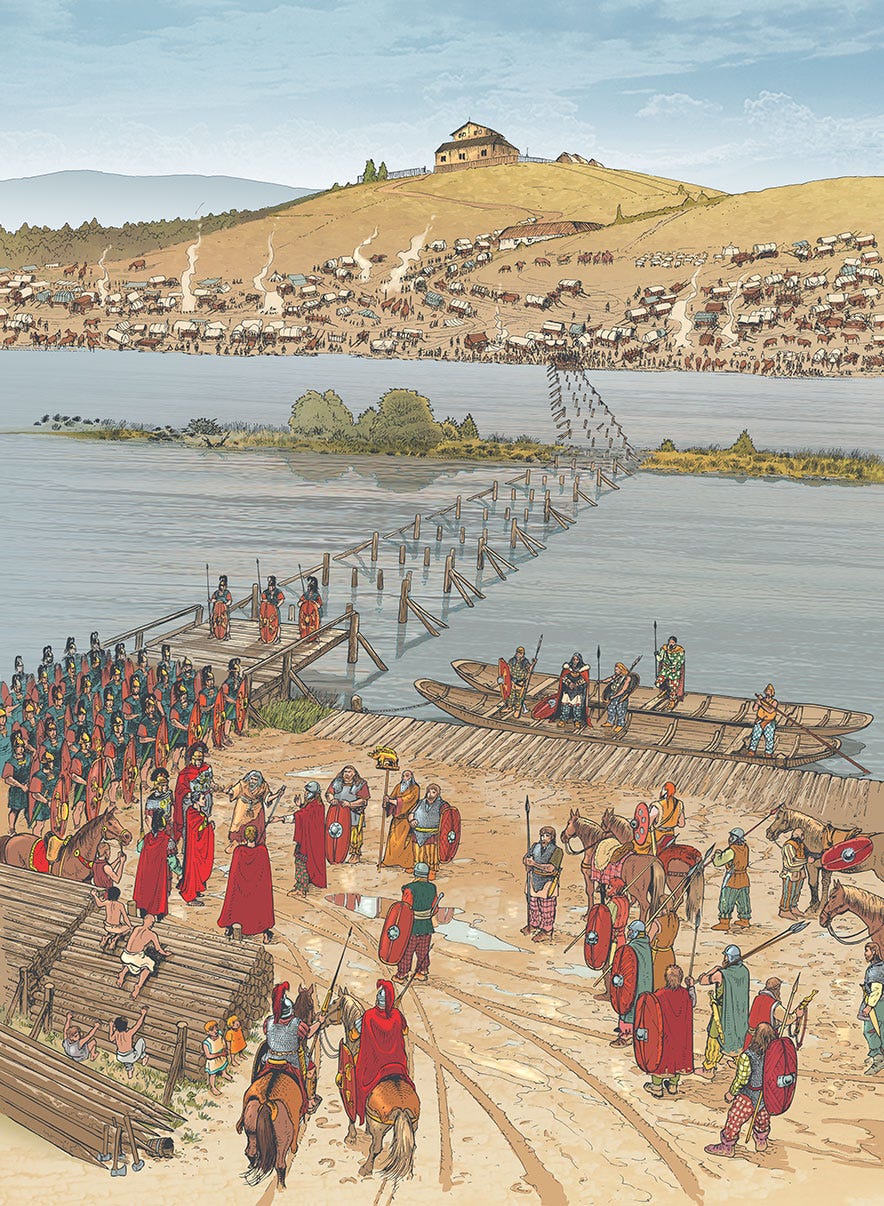

Caesar Crosses the Rhine

Well with that done, Caesar decides he's got to cross the Rhine now. Why on earth would he do such a thing? He explains:

The most cogent reason [to cross the Rhine] was that, as he saw the Germans so easily induced to enter Gaul, he wished to make them fearful in turn for their own fortunes, by showing them that a Roman army could and would cross the Rhine. Moreover, that section of the cavalry of the Usipetes and Tencteri which ... had taken no part in the battle, had now, after the rout of their countrymen, withdrawn across the Rhine into the territory of the Sugambri [another German tribe], and joined them.

So Caesar says he both wants to make a show of force, and he's got some quasi military reasons too, some of these Germans he's just defeated are now taking refuge across the river, rather than submitting to his authority. (Those German ambassadors he seized, by the way, voluntarily submitted to Rome after that defeat and asked to become Caesar's allies).

Caesar also claims, the Ubii (these Trans-rhine Gauls who we mentioned earlier), are pleading with him to come and make a show of force just to scare off the powerful Suebi, who have been harassing the Ubii lately.

So those are all plausible reasons.

But the most plausible of them all is left rather unstated. What better way to make a statement to the most glorious Roman of all, Pompey the Great, and the most Powerful Roman of all, Marcus Crassus, that the Triumvirate of the year 55, though it comprised the same men, was nonetheless a very different sort of triumvirate from the year 59. In that year, Caesar was the Junior partner.

Now, he wanted to send the message, he was their equal: the first Roman commander to cross the forbidding Rhine river with an army.

And for all these reasons, Caesar believes in doing it right.

Because the Ubii here say they have plenty of riverboats, and they're offering to ferry Caesar's army across, they'll make it real easy for him. But here's Caesar's response, which I love:

But he deemed it would neither be sufficiently safe nor worthy of his own and the Romans' dignity, to cross in boats. And so, although he was confronted with the greatest difficulty in making a bridge, by reason of the breadth, the rapidity, and the depth of the river, he still thought that he must make that effort, or else not take his army across.

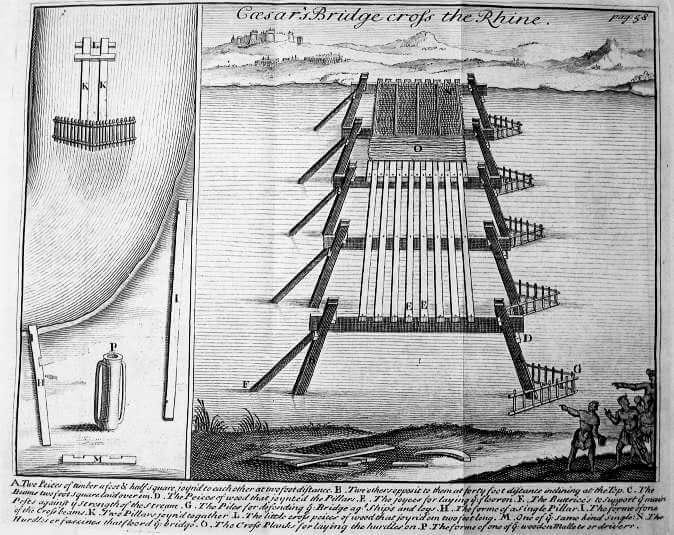

A Bridge is Built

Researchers have narrowed down more or less the spot they think he crossed, it's near what's now Koblenz, in modern Germany. The Rhine is on average about 1300 feet wide there, and 10 feet deep.

And it's characteristic of Caesar that he's going to tell you exactly how he did it (or rather, how his engineers did it)

He proceeded to construct a bridge on the following plan. He took pairs of posts eighteen inches thick, sharpened at the base and cut to be of a length greater than the depth of the river; he had these pairs coupled together at an interval of two feet. These he set fast in the river by means of specialized machinery, and drove them home with pile drivers; not straight up and down like normal piles [... he means such as you might see on a dock in a harbor], but leaning forward at a uniform slope, so that they inclined in the direction of the stream [so he means, these are slanted and pointing downstream]. Opposite to these [that is, downstream from them], at a distance of forty feet from base to base, were planted two posts coupled in the same fashion, slanted against the force and onrush of the stream [in other words, pointing upstream]. On top of every opposing pair of posts were set two‑foot transoms fastened to them at the top filling the interval at which they were coupled [these are the cross beams that will hold the walkway of the bridge], and on each end a brace fastened the beam in place, keeping the two sides apart...1

And, you know, I'll let you read his text if you want to really dig in to all the rest of the details, but it's noteworthy his description here does allow you to reconstruct the basic shape of the bridge pretty accurately. He also puts extra supports downstream to buttress the bridge against the strength of the current, and he also inserts these little independently standing fender posts a few feet upstream, guarding the piles of the bridge, so in case the Germans send logs or rafts down the river to crash into the bridge, these fenders would lesson the blows.

And he says, it took him a mere 10 days, from the time when the wood began to be hauled in, to complete the whole project.

Now, that sounds pretty impressive to me. With no power tools—and really nothing else, building this bridge, this huge engineering marvel, in such a short period of time—well that was itself a colossal show of force to these rude barbarians.

Could your commander in chief do that, with the same tools?

But... Napoleon wasn't that impressed and he comments, "Plutarch Lauds Caesar's bridge over the Rhine, which he considers a prodigious achievement; but it was an entirely unremarkable work which any modern army could construct just as easily."

Hilarious.

Napoleon goes on to spend more than 5 pages discussing his various experiences building bridges in his own glorious campaigns, to prove his point. It's more space than he spends discussing the entirety of book 3...

But, I think this brings up an interesting point. Historians like to comment that Caesar writes things like "Caesar built this bridge, he measured the posts and tied them" etc., as if he was the one actually doing the work.

But of course, they'd say, it was his engineering staff who really made the bridge. And of course it's certainly true that Caesar wasn't trimming down beams and tying transoms himself personally.

But as the Napoleon example shows, a brilliant general like this, often gets autistically deep into the details of important technology. And I think it's consistent with Caesar's incredible detail-oriented personality that he took a direct hand in designing the bridge, or at least, making sure he understood all the essentials his engineers proposed to him. Caesar was also a meticulous grammarian, he wrote a whole book on the subject, we'll hear more about that next time.

And you see this with so many great entrepreneurs: Rockefeller, Onassis, Getty, Jobs, on and on...

So, why shouldn't we expect Caesar to also get personally involved in the details of bridge technology?

And this also relates to a point that Tacitus makes in his work the Germania. He says it was a peculiarity of Rome, as opposed to the barbarians, to lay emphasis on the deeds of an individual general in the conduct of war, rather than the army as a whole (few German tribes operated this way and if they did it was an exception).

What I think he means is, for one thing, this was an essential part of Roman discipline: the commander's will should be what governs the movement of troops on the battlefield, not their individual initiative. It's about obedience.

But another aspect of this distinctive Roman conception of leadership was that the General himself took responsibility for everything that succeeded or failed during a war. If the Persian king's bridge breaks down in a storm (as it did in the invasion of Greece, Herodotus tells the story), well, he has the engineer crucified. It's the engineer's fault. But in the Roman conception, the buck stops with the commander. (at least in theory).

Hence, I think it's fair to say with confidence... that Caesar built the bridge.

Onwards to Britain

Now after all that discussion of the bridge, what follows is a little anticlimactic. The Germans who Caesar intended to fight or intimidate... they scatter and leave right away. The godlike Suebi are reported to be concentrating a huge mass of fighters against him, deep deep into their territory... but Caesar decides, the point has been made, time to move on.

He burns some abandoned villages, cuts down some crops, crosses back into Gaul, and then tears down the bridge - as if just to show that it was such a slight thing to construct he could do it again, anywhere, anytime.

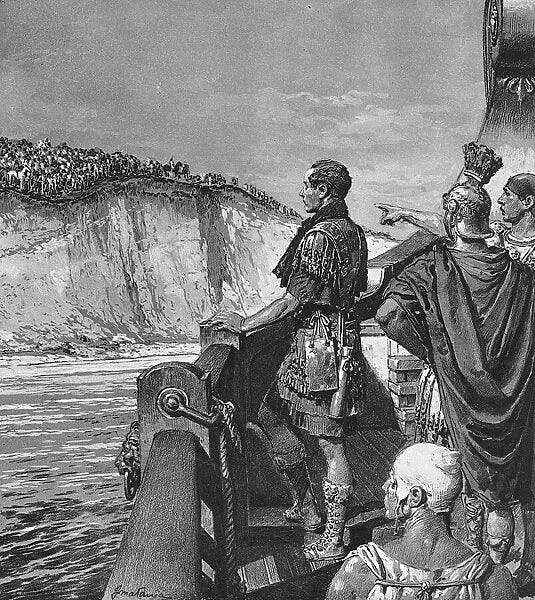

Well it's starting to get late in the summer of 55 by this point, and Caesar decides, I think for reasons we've already mentioned above... that finally, NOW is the time to do the thing that (let's be honest) he's been hankering to do for several years: to head to Britain.

He explains:

Caesar understood that in almost all the Gallic campaigns help had been furnished for our enemies from that quarter [that is Britain, - and recall the many breadcrumbs he's left that we've noted from previous episodes]; and he supposed that, even if the season left no time for actual campaigning, it would still be of great advantage to him merely to have entered the island, observed the character of the natives, and obtained some knowledge of the localities, the harbours, and the landing-places; for almost all these matters were unknown to the Gauls. In fact, nobody except merchants journey there without a good reason..."

Ah... those unsung heroes of ancient military intelligence - the merchants, the risk takers, the cultural adapters, the pioneers, the adventurers, making contacts, discovering routes, brave, now nameless men... But even these people fail him here, so Caesar says - they don't know anything except the sea coast and in general the districts immediately opposite Gaul (whereas he knows it's a big island...)

I think he's probably exaggerating the mystery of Britain here both for storytelling effect and to emphasize his good reason for wanting to explore the place to see if, you know, they might pose some kind a threat (you can note for example that in later chapters he discusses how the Druids of continental Gaul go to Britain to train for years at a time, and the whole religious system there suggests there's actually quite a bit of knowledge and exchange…

Still, for Romans, it's fair to say, Britain is on the edge of the known world. Romans have never been there in any official capacity, even the merchants who go there are overwhelmingly Gauls (Celts that is, the Britons are also a Celtic people)... and come to think of it they may not want to give much information to Romans who could potentially compete with them in the Tin trade for example.

There's also the fact that the ancient conception of the earth was that a great river Ocean encircled the Eurasian-African landmass, and beyond it there were, so to speak, dragons - strange peoples, strange geological phenomena. So you can see the appeal of exploring there.

According to Suetonius, Caesar was led to invade Britain by the hope of obtaining pearls. That's probably not it either.

Once again, we're dealing with... a man whose entire purpose in life is to push his own limits, and also the limits of Roman dominion. And, he's got very good reasons to push those limits this year in particular.

So, no time to waste.

Caesar moves some of his troops into position on the Gallic side of the channel, and he makes his plans known. Pretty soon, he receives an embassy from some of the Celtic tribes of Britain, who've heard of his plans from some merchants, and what do you know! These guys say they're happy to submit to Caesar, he praises them and sends them home. So Caesar's thinking, well this is nice, they come to me, they want peace! Sounds like this Britain expedition might be easier than he thought?

But just in case, Caesar musters two of his legions, two of his best, the 7th and the trusty 10th, and he requisitions [funny] 100 transport ships, as well as a few warships, and another 18 cavalry transport ships for his knights. To make... a dignified appearance to his new allies..

Caesar leaves from near Boulogne, in northern France - Calais is where you usually cross now, but it was under water at the time, nearby Dunkirk as well... the coast has gone out considerably since then.

Caesar makes landfall…

Caesar sets sail around midnight, and by 10am he makes landfall at the White cliffs of Dover, which face the south... Most likely picked this spot ahead of time, he had after all sent a lieutenant out there on a recon mission. And by his choice of this particular landing spot, it seems likely that he was even expecting a warm welcome.

But it it turns out, there must have been some kind of a misunderstanding. The natives aren't so happy to see him:

There Caesar beheld the armed forces of the enemy displayed on all the cliffs. Such was the nature of the ground, so steep the heights which banked the sea, that a missile could be hurled from the higher levels on to the shore. Thinking this place to be by no means suitable for disembarkation, he waited at anchor till the ninth hour [mid afternoon] for the rest of the flotilla to assemble there.

So, seeing the cliffs lined with British soldiers... in a supremely defensible position, Caesar decides to change plans on a sudden... and he steers his flotilla to break out, suddenly, top speed, and head east up the coast, about 7 miles. He disembarks his troops near modern Deal and Walmer, on a beach facing east, without any cliffs overlooking it, in the southeast corner of England.

But the Britons on the cliffs of course can see what he's doing, and they send their cavalry and charioteers along to stop the Romans (more on the charioteers in a moment).

When Caesar gets to the beach, it's a little bit like D-Day.

Disembarkation was a matter of extreme difficulty, for the following reasons. The ships, on account of their size, could not be run ashore, except in deep water [in other words, the transports run aground long before they get to the beach and the troops have to jump out and wade to shore]; the troops — though they did not know the ground, did not have their hands free, and were loaded with the great and grievous weight of their arms —nevertheless had all at the very same time to: leap down from the vessels, to stand firm in the waves, and to fight the enemy. The enemy, on the other hand, had all their limbs free, and knew the ground exceeding well; and either standing on dry land or advancing a little way into the water, they boldly hurled their missiles, or spurred on their horses, which were trained to do this. Frightened by all this, and wholly inexperienced in this sort of fighting, our troops did not press on with the same fire and force as they were accustomed to show in land engagements.

So the Romans are taking serious casualties, they're getting pounded by spears and arrows as they slowly wade to shore. This is all made worse by the fact that Caesar's cavalry transports have gotten delayed by a storm... they're nowhere in sight, nobody's coming to save them.

So here's how Caesar rescues the situation, by thinking quickly:

When Caesar remarked this, he commanded the ships of war (which were less familiar in appearance to the natives, and could move more freely at need) to remove a little from the transports, to row at speed, and to move up on the exposed flank of the enemy; and thence to drive and clear them off with slings, arrows, and artillery. [So the warships are rowing in from the side, and they've got longer range from things like these mid-sized spring loaded catapults, tormenta as the Romans call them]. This movement proved of great service to our troops; for the natives, frightened by the shape of the ships, the motion of the oars, and the unfamiliar type of the artillery, came to a halt, and retired, but only for a little space.

So Caesar's warships are helping out here... but as Caesar tells it, it's an individual act of valor that starts to turn the tide of the battle:

And then, while our troops still hung back, chiefly on account of the depth of the sea, the eagle-bearer [so the army standard bearer] of the Tenth Legion, after a prayer to heaven to bless the legion by his act, cried: "Leap down, soldiers, unless you wish to betray your eagle to the enemy; it shall be told that I at any rate did my duty to my country and my general." When he had said this with a loud voice, he cast himself forth from the ship, and began to bear the eagle against the enemy. Then our troops exhorted one another not to allow so dire a disgrace, and leapt down from the ship with one accord. And when the troops on the nearest ships saw them, they likewise followed on, and drew near to the enemy.

Do you think one man can turn an entire battle? I believe this. And this act of the eagle bearer... if that doesn't show you the incredible power of symbols... I don't know what will.

But even with this brave standard bearer leading the charge into the waves, it's takes a very difficult battle to secure the landing. The Romans finally get enough infantry to shore to form ranks and charge the enemy and put them to flight. But since they don't have any cavalry, and the Britons here are either mounted or in Chariots, the Romans can't chase them very far.

But... all the same, with difficulty, Caesar thus establishes a beachhead.

The native leaders now come with another embassy, tail between their legs, and they say, "ah forgive us Caesar, you know, it was the rowdy multitude that forced our hand..." and Caesar admonishes them for going back on their word, but he says, he'll forgive them... if they supply some hostages.

So Britons get about doing this, some hostages they turn over immediately, some they go off to fetch from a few days journey away.

Nature is not kind to the Romans

Now, at this point, we're in late August or early September... and the English channel around this time of year can experience very sudden, violent storms. And a few days later, Caesar and the Romans see the cavalry transport ships finally arriving off in the distance, when ... a sudden squall blows up and drives them away, and they just retreat back to the continent and give up. And Next, that very same night, it was a full moon, so the tide was extra high, and the stormy seas engulf the Roman fleet, both the ships drawn up dry on the beach and those lying at anchor in the bay, and basically every ship in the fleet is damaged, disabled or completely smashed.

Now, all of a sudden, the Romans are in a foreign land, with just two legions, so maybe 9,000 men... a force big enough to be hard to feed, but small enough to be contemptible to a coalition of native tribes... and Caesar didn't bring enough food for a long campaign, much less enough to last through the winter, and now they have no way of escaping... in other words, they've got a big problem.

The native Britons perceive this immediately.

The requested hostages immediately stop trickling in to Caesar's fort. Then, hostages and ambassadors in his camp start to slip away little by little and escape.

Caesar knows what's going on.

And he starts furiously buying up, or seizing, grains from the surrounding countryside. He starts chopping down trees, salvaging the bronze and timber from smashed ships, he gets his soldiers repairing the fleet, day and night.

But one day when the Seventh legion is out foraging for supplies... the outposts guarding the ramparts of the camp report to Caesar... they see a large dust cloud rising from the direction in which the Seventh headed out that morning.

Here's Caesar:

Caesar suspected the truth — that some fresh design had been started by the natives. He ordered the cohorts who were on outpost to proceed with him in the direction of the commotion, two of the others to relieve them on outpost, and the rest to arm themselves and follow after him as soon as possible. When he had advanced some little way from the camp, he found that his troops were being hard pressed by the enemy and were holding their ground with difficulty: the legion was crowded together, while missiles were being hurled from all sides. The fact was that the grain had been harvested from the rest of the neighbourhood, and only one part remained - the enemy, guessing that our troops would head for that spot, had hidden by night in the woods; then, when the men were scattered, put their arms down, and began harvesting grain, the enemy suddenly attacked them. They had killed a few, throwing the rest into confusion before they could form up, and at the same time surrounding them with horsemen and chariots.

So Caesar snaps into action. He comes up on his troops of the 7th legion, and finds they are hard pressed. They're also out of their element because they are up against this novel form of fighting that the Britons employ, which Caesar describes here, listen to this:

Their manner of fighting from chariots is as follows. First of all they drive in all directions and hurl missiles, and so by the mere terror that the teams inspire and by the noise of the wheels they generally throw enemy ranks into confusion. When they have worked their way in between the troops of cavalry, they leap down from the chariots and fight on foot. Meanwhile the charioteers retire gradually from the combat, and dispose the chariots in such fashion that, if their own warriors are hard pressed by the host of the enemy, they may have a ready means of retirement to their own side. Thus they show in action the mobililty of cavalry and the stability of infantry; and by daily use and practice they become so accomplished that they are ready to gallop their teams down the steepest of slopes without loss of control, to check and turn them in a moment, [and, listen to this level of showmanship... the riders are also so skilled they can] run along the pole, stand on the yoke, and then, quick as lightning, dart back into the chariot.

This sounds like something straight out of Homer, as Caesar knows, Bronze age warlords riding to battle in chariots, hopping out to fight, hoping back in to go somewhere else... War chariots were by this time out of fashion in Greece, Rome, and Gaul... but we do have archaeological evidence of these types of chariots continuing on in use in England and Ireland for much longer.

And you can see why the Britons would change their mind, about making peace with the Romans, once they see Caesar is vulnerable. They're probably thinking, if they destroy this invasion force, Romans are going to think twice about meddling in Britain again.

But Caesar's quick action—rescuing the greatly distressed Seventh legion—saves the day. He puts the enemy into confusion and makes them regruop, and it's just enough time for his own men of the Seventh to regain their own wits and form up ranks with the new cohorts Caesar's brought, and so the Britons retire... Caesar withdraws to his camp.

Well now, the Britons start gathering their fighters from all around the countryside and sending messages out, the Romans are weak, it's time to strike before they get away and bring back their friends!

And within a few days, there's a large force of British infantry and horsemen assembled, and they make an assault on the camp.

But... these kinds of open full army vs full army battles, where infantry plays a major role, these are exactly the kind of confrontations where the Romans shine. And Caesar marches out and defeats them. He also has about 30 cavalry now (The British returned a Gallic ambassador of his they had captured earlier, named Commius, and Commius had brought a few knights with him). So, 30 cavalry is just enough to terrorize a medium sized force retreating in panic and disorder and chase and kill a few men and prevent them from regrouping.

Victory to Caesar.

Caesar heads back

At this point, the natives send deputies [funny] again to treat for peace. Caesar doubles the amount of hostages he requires. But then he says, “You guys are going to have to ship them over to me in Gaul” because his ships are finally ready, and he needs to get the heck out of there before the autumnal equinox (around our September 22). So he manages to cram all his men into a reduced number of ships, and sails at last back to Gaul.

Now... looking at the facts, it would probably be overly generous to consider this mission a victory. Really, you could argue, Caesar didn't accomplish much except losing a few men and irritating some locals. But he did once again prove his incredible ability to rescue a dire situation, both in forcing the amphibious landing, and in staving off utter destruction once his fleet had been wrecked.

Military victory or not, it's a huge political win for him. The senate, when the reports come in, declare for Caesar an unprecedented, amazing, 20 day long thanksgiving celebration. Twice as many as Pompey got for his Mithridatic war victory... and 15 more than Caesar got for his victories in 57 against the Nervii.

So... maybe you'd say, Mission accomplished?

But, if you're Caesar, you can just feel it in your bones...you haven't proven what you're capable of in Britain. These people clearly haven't experienced the might of Roman arms. And what does he have to show for it really? What new trade routes have been opened, what riches has he discovered, what firm allies has he won?

If you're a careful student of Caesar you just know...He'll be back.

But that's a story for next time.

If you enjoyed this, and want to see more Caesarian greatness in our world today, in all its complexity... do us a favor and leave us a good review somewhere, tell a friend, and the next time you're faced with a dire situation, put in just that much more effort. Make the Proconsul proud.

Thanks for listening, stay strong, Stay Ancient, this is Alex Petkas, until next time.

Here’s the full text:

So, as they were held apart and contrariwise clamped together, the stability of the structure was so great and its character such that, the greater the force and thrust of the water, the tighter were the balks held in lock. These trestles were interconnected by timber laid over at right angles, and floored with long poles and wattlework. And further, piles were driven in aslant on the side facing down stream, thrust out below like a buttress and close joined with the whole structure, so as to take the force of the stream; and others likewise at a little distance above the bridge, so that if trunks of trees, or vessels, were launched by the natives to break down the structure, these fenders might lessen the force of such shocks, and prevent them from damaging the bridge.

Wonderful summary…Thank you so much!

I listened to it last night. Loved it, may be my fave of the series so far!

Scrolling through here, it's great to see images and maps. That always helps put things in context because a lot of the names are unfamiliar.

Keep up the good work! 💚 🥃