Caesar At Sea — De Bello Gallico - Part 3

Part 3 of an 8 part series on Caesar's Gallic Wars...

Caesar faces enemies at home and on sea, in part 3 of our series on Caesar’s masterwork of psychology, strategy, and propaganda: On the Gallic War (De Bello Gallico).

This is a world-history making story (the conquest of what’s now modern France), told by a world-history making storyteller.

Caesar entered Gaul as a mere politician. He returned 9 years later as a conqueror - and an enemy of the state. He tells how it all happened with his own pen.

In this episode:

Caesar faces the sea-faring people of Veneti

Caesar plays political games

Ship technology, and military strategy

This episode is sponsored by Ancient Language Institute. If you want to be like Caesar, you should learn an ancient language (Caesar knew Greek in addition to his native Latin). The Ancient Language Institute will help you do just that. Registration is now open (till August 10th) for their Fall term where you can take advanced classes in Latin, Ancient Greek, Biblical Hebrew, and Old English.

You can listen to the episode here:

Stay Ancient,

Alex

Announcement: I’d love to see you in Ecuador next month (August 22-25) for an amazing event I’m organizing with some friends. More info Here at this post below:

How Empires are Built

"Plato’s Academy, *by far* the most successful philosophy school in antiquity, was not primarily a set of ideas, but a self-perpetuating, decentralized network, united by a common vision." I’m co-organizing and speaking at an event August 22-25 in Ecuador. I’d love to meet you there - or some other time.

Transcript

Imagine you're in a little Swiss hamlet in the Alps, and you wake up to this:

Several days had passed in winter quarters, and Galba had given orders for grain to be brought in from the neighbourhood when all of a sudden his scouts informed him that in the night every soul had withdrawn from that part of the town which he had granted to the Gauls, and that the heights overhanging were occupied by an enormous host of Seduni and Veragri.

— Caesar, “Gallic War” (Book III)1

More trouble for Caesar by land and by sea, in this, book 3, of the Gallic War commentaries.

I'm Alex Petkas and you are listening to the Cost of Glory, where it is our mission to retell the lives, deeds, and characters of the greatest Greek and Roman heroes. This is part 3 of 8 of our series on one of Rome's greatest wars, Caesar's conquest of Gaul.

The Cost of Glory is produced in collaboration with Infinite Media.

In this episode, we are returning once again to a book that made nations. A book read and admired by countless leaders, Machiavelli, Washington, Hamilton, and commented on by Napoleon (who we'll hear from later)—men who used this book to forge their own paths to greatness.

In Chapter 3 or let's call it Book 3 of On the Gallic War, Caesar challenges the great seafaring nation of the Veneti on the Atlantic, among other campaigns. If you like diving into the kind of technology that wins wars, this is a great episode for you, and also there are some great insights into how to manage your subordinates and bring out the best in them. But Caesar also hints, very briefly, at some developments on the home front. And I want to give you a little idea of what's going on in Rome at this time.

First though—and this is actually related to the homefront question—Caesar opens the book with his legate, this man Galba, coming very close to disaster in the winter in the Alps.

It's interesting because this activity actually happens late in the year 57, so it technically should have belonged in the previous book, because Caesar organizes these books by campaign season years. But he wanted to end the last book with the news of this unprecedented 15-day thanksgiving celebration for his victories so far... to end on a high note.

Remember, this is also war propaganda.

So let's start by taking a look at what happens to Galba in the opening of this book.

Galba faces Danger

The man, by the way, is Servius Galba, who later runs for the consulship for the year 49, and failing that—even though he was a loyal supporter of Caesar and Caesar loyally supported him (tried to pull a lot of strings to get him elected)—ends up joining the conspiracy of Brutus and Cassius, and becomes one of the men who stabs Caesar in the senate in 44 BC.

That's all later though. Right now, Caesar's going to do him a favor and he gives the man the spotlight and shows how he deals with a very difficult situation.

Galba camps his forces (he's got 1 legion, the 12th), in a mountain pass in the Alps. It's in the territory of the Allobroges, and you could say, if you're a Roman, that this is technically in the Roman province, it's the borderlands between Transalpine and Cisalpine Gaul. But the people of the mountains might have a different opinion of whose territory it really is... and mountain dwellers are hard to tame.

In fact, Galba right now is near some of the highest mountains in Europe. He's at Octodunum, which is now called Martigny, it's at the foot of Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa, and the Matterhorn2.

And the reason Galba is there is to secure the Great St. Bernard Pass, to make transit between Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul easier for diplomatic missions, merchants and of course the occasional army led by a commander bent on becoming the First Man in Rome.

So, Galba has gotten comfortable here because he's captured a few native forts and exchanged hostages with the local elites. That's usually a guarantee of good behavior.

But on this particular morning, the camp wakes up to find that the native friends that they just concluded a peace with have vanished, and that there is a large force of armed Gauls lining the very steep slopes around the camp.

Caesar explains their reasoning:

Several causes had contributed to make the Gauls suddenly adopt the plan of renewing the war and crushing the legion. In the first place, they despised the small numbers of a [single] legion, from which... two cohorts had been withdrawn, and a considerable number of private soldiers sent off to seek supplies. [Galba again, kind of let his guard down] In the second place, they supposed that, because of the disadvantage of position, since they themselves would charge down from the heights into the valley and hurl their missiles, not even their first onset could be withstood. Moreover, they were indignant that their children had been taken away from them under the title of hostages; and they were convinced that the Romans were endeavouring to seize the peaks of the Alps and to add those districts to their neighbouring Province, not only for the sake of the routes, but to secure a permanent occupation.

I love how Caesar is so frank and honest about the natives' perspective, throughout this work. He'll say, they believe the Romans are trying to conquer them... and that is basically what's happening, isn't it? For all that this is a sort of propaganda work, Caesar maintains this very clear perspective, untainted by sentimentality.

Well, here's what Galba does:

[Galba] therefore summoned with speed a council of war, and proceeded to ask for expressions of opinion. The danger that had arisen was as serious as it was sudden and unexpected, and indeed by this time almost all higher ground was seen to be packed with a host of armed men, while, with the communications interrupted, reinforcements could not be attempted nor supplies brought up. In the council, therefore, the chance of safety was almost despaired of, and not a few opinions were expressed in favour of abandoning the baggage, making a sortie, and striving to win safety by the same routes which had brought them thither. None the less, the majority decided to reserve this expedient to the final emergency, and meanwhile to await the issue and defend the camp.

They don't have to wait long.

The Gauls charge down the hill, they throw their stones and javelins at the men on the Roman ramparts from high above, and Galba's got the camp only partially fortified.

The fighting is hard... The Romans are so short on defenders that even the wounded can't afford to take a break from the fighting.

Here’s what happens next (see if you can remember the man Caesar names first here):

The fighting actually went on for more than six hours on end, and not only the strength but the missiles of the Romans were failing; the enemy were pressing on more fiercely, and beginning, as our energies slackened, to break down the rampart and fill in the trench. At this juncture Publius Sextius Baculus, the senior centurion [whom we have mentioned before as disabled by several wounds in the battle with the Nervii in book 2], and with him Gaius Volusenus, a military tribune, a man of great sagacity and courage, hastened to Galba, and informed him that the only hope of safety was to try the last expedient in making a sortie. Galba accordingly summoned the centurions, and speedily instructed the troops to make a short pause in the fighting, and merely to intercept the missiles discharged against them, and to refresh themselves after their effort; then, upon a given signal, to burst from the camp and place all hope of safety in courage.

And that's exactly what they do, they burst out of the camp gate, sweep around and cut off the attackers, and this surprise change of energy in the battle overwhelms and terrifies the Gauls, and they end up fleeing.

Caesar says that the Romans (which would have been less than 4,000 men) ended up slaughtering some 10,000 of the 30,000 who had attacked the fort.

And they were following the advice of this fine soldier Publius Sextius Baculus, who fought bravely against the Nervii despite receiving many wounds. Still in action there. Once again, you've got to admire Caesar giving credit to his talent.

The next day, the Romans retreat to safer country down the valley in the plains, to finish the winter out.

War breaks out, led by the Veneti

Well, now Caesar comments, as he has before and will again several times, that at last, “all Gaul is pacified”. And he busies himself with provincial matters in Illyria.

But this peace, of course, doesn't last very long:

But at this point war broke out suddenly in Gaul, of which the cause was as follows. Publius Crassus the younger with the Seventh Legion had been wintering by the Ocean in the country of the Andes. As there was a lack of grain in those parts, he dispatched several commandants and tribunes into the neighbouring states to seek it. Of these officers [these names are not that important] Titus Terrasidius was sent among the Esubii, Marcus Trebius Gallus among the Curiosolites, Quintus Velanius with Titus Silius among the Veneti.

These Veneti [these guys are important] exercise by far the most extensive authority over all the sea‑coast in those districts, for they have numerous ships, in which it is their custom to sail to Britain, and they excel the rest in the theory and practice of navigation. As the sea is very boisterous, and open, with but a few harbours here and there which they hold themselves, they have as tributaries almost all those whose custom is to sail that sea. It was the Veneti who took the first step, by detaining Silius and Velanius, supposing that through them they should recover their own hostages whom they had given to Crassus. Their authority induced their neighbours — for the Gauls are sudden and spasmodic in their designs — to detain Trebius and Terrasidius for the same reason, and, rapidly despatching deputies among their chiefs, they bound themselves by mutual oath to do nothing save by common consent, and to abide together the single issue of their destiny. Moreover, they urged the remaining states to choose rather to abide in the liberty received from their ancestors than to endure Roman slavery. The whole sea‑coast was rapidly won to their opinion, and they despatched a deputation in common to Publius Crassus, bidding him restore their hostages if he would receive back his own officers.

So the area Crassus is in is basically the northern section of the Atlantic Coast on the western seaboard of France, the southern reaches of the area now known as Brittany. The key nation here is the Veneti, who Napoleon calls “The People of Vannes”, Vannes being a major city of the area, that of course takes its name from these very Veneti.

And it's interesting... this taking hostages strategy really doesn't seem to work all that well on the Gauls. The hostages would most likely be sons of the nobles, so as in the former case in the Alps either the Gauls trust the Romans not to murder their hostages (of course the Veneti here have got their own hostages which is noteworthy) or, maybe, they consider even their own not-yet-of-age sons to be sort of legitimate combatants in this epochal conflict for liberty. I think either way it's really interesting they're willing to put their own children at great risk here...speaks to the fierce spirit of these people.

Now Caesar comments here, that he gets the message from young Crassus, and he sends orders to him to get to work building ships... and just in passing he notes, "Caesar had to be away rather longer..."

Caesar as Politician

That little phrase covers a multitude of sins... and it's worth remembering the incredible storm of Roman politics that Caesar is navigating remotely right now, which makes his achievements in Gaul all the more astonishing.

The year now is 56 and Caesar had to do some major politicking that we'll cover more in his biography (we already discussed it in the life of Crassus and Pompey). Basically, Caesar's 5 year command is scheduled to end in 54. So you might think he's still got some time to not have to worry about politics. But the Senate is legally bound to assign proconsular commands before consuls for the following year are elected. In other words, the proconsular (provincial governor assignments) for 54, get taken up by the consuls of the year 55, but those assignments have to be picked in the year 56.

So what's detaining Caesar from bringing the war personally to the Veneti right now is a semi-secret political meeting that he organizes at Luca (in Italy) but just inside his province, where he corrals all his supporters and many men on the fence in the Roman senate (they come to him... very notably), and the other two triumvirs Pompey and Crassus are there of course, and they make a plan to dominate Roman politics for the following year, including a plan to make sure Caesar gets his command extended another 5 years. Many of Caesar's bitter enemies, powerful enemies in the senate, are trying to dislodge him from leading the war in Gaul right now.

Well, the triumvirs end up really twisting the orator Cicero's arm, and get him to support their plan.

Cicero you might remember from earlier biographies was up to this point a staunch opponent of Caesar, (though not a mortal enemy). But they get him to change his tune and he makes a famous speech, On the Consular Provinces in the spring of 56. It's a great speech and a lesson in what a political reconciliation of enemies looks like. Here's a quote from that speech to give you a sense3:

The war with Gaul, O conscript fathers, has been carried on actively since Gaius Caesar has been our commander-in-chief; previously, we were content to act in defence, and to repel attacks. For our generals at all times thought it better to limit themselves to repulsing those nations, than to provoke their hostility by any attack of our own. Even that great man, Gaius Marius, whose godlike and amazing valour came to the assistance of the Roman people in many of its misfortunes and disasters, was content to drive back the enormous multitudes of Gauls who were forcing their way into Italy, without endeavouring to penetrate into their cities and dwelling-places....

This is an interesting contrast, listen to this:

But I see that the intentions of Gaius Caesar are very different. For he thought it his duty, not only to wage war against those men whom he saw already in arms against the Roman people, but to reduce the whole of Gaul under our dominion. Therefore, he fought with the greatest success against those most valiant and powerful nations the Germans and Helvetii; and the other nations he terrified and drove back and defeated, and taught them to yield to the supremacy of the Roman people, so that those districts and those nations which were previously not known to us - neither by any one's letters, nor by the personal account of any one, nor even by vague report - have now been overrun by our own general, by our own army, and by the arms of the Roman people.

So note there, Cicero is basically giving his approval not only to a war of defence, but a war of offence... on pre-emptive grounds. Pretty striking. Finishing up here:

Previously, O conscript fathers, we have only known the road into Gaul. All other parts of it were possessed by nations which were either hostile to this empire, or treacherous, or unknown to us, or, at all events, savage, barbarian, and warlike; no one ever existed who did not wish these nations to be crushed and subdued: nor has any one, from the very first rise of this empire, ever carefully deliberated about our republic, without thinking that Gaul was the chief source of danger to this empire. But still, on account of the power and vast population of those nations, we never before have waged war against all of them; we have always been content to resist them when attacked. Now, at last, it has been achieved that there should be one and the same boundary to our empire and to those nations.

And Cicero goes on to reason, that even though Gaul is mostly pacified, and even though he has his own personal disagreements with the man, it's in the interests of the Republic to let the same man who brought the war also bring permanent peace and stability to the region.

So after that speech, the senate votes to leave Caesar's provinces untouched. They also vote meanwhile, at Cicero's instigation—but notably against some determined opposition from the hardliner conservatives like Cato and Domitius—not just to give Caesar that 15-day thanksgiving celebration, but also to supply his war effort through the state treasury (which is a big win for Caesar), and to send him additional legates to help.

So Caesar, in the midst of his brilliant successes in Gaul...also wins an amazing victory on the home front. You can see why he was so impressive to his contemporaries.

And with that wrapped up, Caesar heads for the Atlantic coast.

Caesar at the Atlantic

He gets there, of course, quicker than they expected him.

The Veneti and likewise the rest of the states were informed of Caesar's coming, and at the same time they perceived the magnitude of their offence — they had detained and cast into prison deputies, men whose title had ever been sacred and inviolable among all nations. Therefore, as the danger was great, they began to prepare for war on a corresponding scale...

So he pauses there to remind you that this is a just war and the Veneti’s offense was egregious—that's important.

And here he's going to tell you why this is going to be a particularly hard victory for him to pull off:

and especially [the Veneti took measures] to provide naval equipment, and they were filled with all the more hope because they relied much on the nature of the country. They knew that on land the roads were intersected by estuaries, that our navigation was hampered by ignorance of the locality and by the scarcity of harbours, and they trusted that the Roman armies would be unable to remain long in their neighbourhood by reason of the lack of grain. Moreover, they felt that, even though everything should turn out contrary to expectation, they were predominant in sea‑power, while the Romans had no supply of ships, no knowledge of the shoals, harbours, or islands in the region where they were about to wage war; and they could see that navigation on a land-locked sea was quite different from navigation on an Ocean very vast and open. Therefore, having adopted this plan, they fortified their towns, gathered grain from the fields, and assembled as many ships as possible in Venetia, where it was known that Caesar would begin the campaign.

So this is a kind of classic Roman challenge. They are thinking, these Romans may know how to sail on the Mediterranean, where you can lose some ships in a storm at sea, but it's nothing like the furious Atlantic. Have you seen videos of some of the waves that you can get on the Atlantic coast of Portugal? Or the basque country of France? Atlantic storms can kick up waves 50, 60, 90 feet high in the right conditions...there's just no comparison.

But...who else was it that underestimated Roman maritime capabilities? The Carthaginians, in the first Punic Wars.

But there Caesar’s given you some of the reasons why this nation of the Veneti are feeling good about their chances in the war. Plus, they've got a long list of allies Caesar gives, and I won't read them all here but it includes the Namnetes, the people of Nantes, and very notably, another breadcrumb presaging something else Caesar has in mind...they send to that mysterious isle of Britain for some auxiliaries...

We'll hear more about the pretty formidable military defences of the Veneti in just a minute. But this is what Caesar is thinking:

The difficulties of the campaign were such as we have shown above; but, nevertheless, many considerations moved Caesar to undertake it. Such were the outrageous detention of Roman knights, the renewal of war after surrender [remember they concluded a treaty with young Publius Crassus], the revolt after hostages given, the conspiracy of so many states — and, above all, the fear that if this district were not dealt with the other nations might suppose they had the same liberty. He knew well enough that almost all the Gauls were bent on revolution, and could be recklessly and rapidly aroused to war; he knew also that all men are naturally bent on liberty, and hate the state of slavery. [Again, he's very honest about his opponent's moral seriousness here]. And therefore he deemed it proper to divide his army and disperse it at wider intervals before more states could join the conspiracy.

So Caesar sends off Labienus to the East, Crasuss to the south, to Aquitaine, and Sabinus north towards Normandy (more on how the last two fared later on). And noteworthy here also, he puts young Decimus Brutus in charge of the fleet (he's also got some Gallic allies building ships for him, Decimus commands those as well). Decimus Brutus is not the famous Brutus, but all the same he ends up being one of the conspirators who eventually assassinates Caesar, and then he plays a pretty important role in the civil war with Antony and Octavian that followed. It's also noteworthy here, he calls Decimus and Crassus “Young” here to designate, these are promising young men who are not yet 30 years old and haven't hold the requisite office of Quaestor and so therefore haven't even joined the senate. Once again, Caesar's got an amazing talent pool4.

The Territory of the Veneti

Now listen to how Caesar describes the territory of the Veneti and their allies, and he's doing some great storytelling here, setting it up by first describing all the challenges, and you come off wondering, “how is this even going to be possible?”

The Veneti are a sea people, and for their strength they rely on heavily fortified coastal cities which Caesar describes here:

The positions of the strongholds [of the Veneti etc.] were generally of one kind. They were set at the end of spits of land and promontories, so as to allow no approach on foot, when the tide had rushed in from the sea — which regularly happens every twelve hours — nor in ships, because when the tide ebbed again the ships would be damaged in shoal water. [Have you ever seen pictures of Mont St. Michel in France, that fortress that's sometimes an island, sometimes accessible by the beach, depending on the tide? This is close to that area. The Atlantic tides in France are famous, they can vary by as much as 49 feet of sea level...] Both circumstances, therefore, hindered the assault of the strongholds; and, whenever the natives were in fact overcome by huge siege-works — that is to say, when the sea had been set back by a massive mole built up level to the town-walls — and so began to despair of their fortunes, they would simply bring close inshore a large number of ships, of which they possessed an unlimited supply, and take off all their stuff and retire to the nearest strongholds, there to defend themselves again with the same advantages of position.

So they are very hard to take either by land or sea. Caesar adds to this the difficulties they face from the terrain the difference in ship technology:

They pursued these tactics for a great part of the summer the more easily because our own ships were detained by foul weather, and because the difficulty of navigation on a vast and open sea, with strong tides and few — nay, scarcely any — harbours, was extreme.

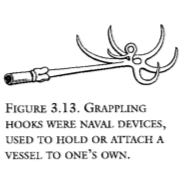

Not so the ships of the Gauls, for they were built and equipped in the following fashion. Their keels were considerably more flat than those of our own ships, that they might more easily weather shoals and ebb‑tide. Their prows were very lofty, and their sterns were similarly adapted to meet the force of waves and storms. The ships were made entirely of oak, to endure any violence and buffeting [I believe Mediterranean ships are more typically made of softer woods like Pine which works in the Mediterranean]. The cross-pieces were beams a foot thick, fastened with iron nails as thick as a thumb. The anchors were attached by iron chains instead of [rope] cables. Skins and pieces of leather finely finished were used instead of sails, either because the natives had no supply of flax and no knowledge of its use, or, more probably, because they thought that the mighty ocean-storms and hurricanes could not be ridden out, nor the mighty burden of their ships conveniently controlled, by means of sails. When our own fleet encountered these ships it proved its superiority only in speed and oarsmanship; in all other respects, having regard to the locality and the force of the tempests, the others were more suitable and adaptable. For our ships could not damage them with rams (they were so stoutly built), nor, by reason of their height, was it easy to hurl a pike, and for the same reason they were less readily gripped by grapnels. Moreover, when the wind began to rage and they ran before it, they endured the storm more easily, and rested in shoals more safely, with no fear of rocks or crags if left by the tide; whereas our own vessels could not but dread the possibility of all these chances.

So if the tide goes out, the Veneti's ships just sit there on the beach in these flat bottomed ships, and they can just wait it out in tall, sort of mini-fortresses, and they'll be sailing again in 12 hours or so. Roman ships on the other hand will get damaged or roll over, they have to be very careful to follow the tide out.

So almost to prove his point of how hard this is, Caesar tells how, he himself gets busy taking them on by land... and he starts capturing the odd fortress here or there, but it's kind of pointless, because the Veneti will just escape and regroup to another fortress, and they've got lots of them. Caesar decides to wait for Decimus and the fleet, that's assembling nearby.

The Battle of Morbihan

But when the fleet arrives, it's still not clear how the Romans are supposed to make any progress against these expert mariners. Caesar explains:

For our commanders knew the enemy could not be damaged by the ram; while, even when turrets were set up on board, the lofty sterns of the native ships commanded even these, so that from the lower level missiles could not be hurled properly, while those discharged by the Gauls gained a heavier impact.

But they eventually come up with a new kind of strategy, and they wait for a day where the weather is good and engage in a battle, and here's what they do:

One device our men had prepared to great advantage — sharp-pointed hooks inserted and fastened to long poles, in shape not unlike siege-hooks. When by these contrivances the halyards which fastened the yards to the masts were caught and drawn taut, the ship [the Roman ship that is] was rowed hard ahead and they were snapped short. [The yards are the horizontal wood sail holders, so it's sort of like hooking a cable attached to your pickup truck up to a stop sign, and then driving away. That's what they do with the Veneti's sails] With the halyards cut (these are the ropes on the sail], the yards of necessity fell down; and as all the hope of the Gallic ships lay in their sails and tackle, when those were torn away all chance of using their ships was taken away also. [Again the Romans are not so great with the sailing stuff, but they're really strong rowers, and the Veneti are the exact opposite]. The rest of the conflict was a question of courage, in which our own troops easily had the advantage — the more so because [this is very important] the engagement took place in sight of Caesar and of the whole army so that no exploit a little more gallant than the rest could escape notice. The army, in fact, was occupying all the hills and higher ground from which there was a near view down upon the sea.

Caesar and his officers are standing there on the shoreline like spectators... and he's got a great eye for the psychology of his sailers there—The Big Man is watching.

It's worth thinking about there... the gaze of the general if ever your operation becomes so big, that your guys aren't periodically subjected to the power of your “gaze” so to speak... well you should probably change something. Because... its not just about having someone, say management, looking at them, it's about the general himself doing it.

Going on:

When the yards had been torn down as described, and each ship [of the Veneti] was surrounded by two or three [of our own], the troops strove with the utmost force to climb on to the enemy's ships. [So the Romans with their smaller ships are piling on these Venetian ships like hyenas on a lion...and...] When several of them had been boarded, the [other] natives saw what was coming; and, as they could think of no device to meet it, they hastened to seek safety in flight. And they had headed all their vessels down the wind, when suddenly a calm so complete and absolute came on that they could not stir from the spot. This circumstance was in the highest degree fortunate for the settlement of the business, for our troops pursued and boarded the vessels one by one, with the result that of all the number very few, when night came on, reached the land. The battle, indeed, lasted from about the fourth hour to sunset.

So where did the Veneti go wrong? Well they studied their enemies... but they paid more attention to the Romans' unique weaknesses, rather than their unique strengths: rowing, technology, and of course, most importantly and most Roman of all... methodical, brute determination.

And here's the result:

This engagement finished the campaign against the Veneti and the whole sea‑coast. For, on the one hand, all the fighting men, nay, all the older men who had any sagacity or distinction, had assembled there; on the other, they had collected in one place every single ship they had anywhere; and after such losses the rest of their men had no point to retire to, no means of defending the towns. Accordingly they surrendered themselves and all they had to Caesar.

Caesar decides however that their punishment should be particularly severe so that in the future the Gauls should take more consideration of respecting what the Romans would consider international law, that is, the inter-state customs protecting envoys. And so he has all the town councilors (the leadership, the decision makers), executed, and sells the rest of the people as slaves.

You'll be pleased to hear that this area today does have a lively Breton-speaking community, that's the language descended from the old Celtic days. But that doesn't make up for the fact that, Caesar's treatment was even in his own day seen as uncommonly harsh. Napoleon in fact criticizes him for it, here's what he says in his commentaries:

One can only despise Caesar’s treatment of the Senate of Vannes. This people had not revolted; they had provided hostages and promised to live quietly, but they were in possession of all their rights and liberties. They had indeed given Caesar grounds to make war against them, but not to violate the law of nations in their case and to misuse his victory in so atrocious a way. This conduct was not just; still less was it politic. Such means never achieve their aim; they anger and disgust the nations. The punishment of a few chief people is all that justice and policy permit; it is an important rule to treat prisoners well. The English broke this moral and political rule by placing French prisoners on hulks, which has made them hated throughout the continent.

— from Napoleon's Commentaries on the Wars of Julius Caesar: A New English Translation (link)

Napoleon there obviously speaking from his own experience, but I'll let you decide for yourself whether you think it was justified or prudent. It's worth noting that we do find a few Veneti and other tribes from this region joining other revolts later in the story.

And probably not an insignificant number of these people he sold off were not condemned to a life of servitude, but ransomed by friends or kinsman. The point is, they were sold, and Caesar got the money for it. Did he need the money? Especially after capturing the very rich cities of these men of the coast - they were rich through their trade with Britain...

He might have realized how close he came to getting undermined at home by his enemies this year, and he might have been wanting to build up a big war chest... for the war on the home front, that is, a war waged with bribes and favors to coerce his opposition.

Well, anyway, that's the one main accomplishment of Caesar himself in this year of campaigning, and considering his victories on the political front, I think that alone is pretty impressive. But he does close the book with two case studies which highlight that fact that he's got some talented men working under him capable of independent initiative.

They're worth treating briefly because Caesar is also including them for the leadership lessons they contain.

Lessons in Leadership #1: The Story of Sabinus

First up is Quintus Titurius Sabinus, the guy he sent north to Normandy. Now, Sabinus ends up making a fatal, tragic mistake in a later book... but the fact that he performs so competently here in this book shows just how hard won Caesar's ultimate victory over Gaul was, that men like this could also end up getting defeated disastrously by these very crafty Gauls.

Now Sabinus is camped near modern day Cherbourg, on the tip of the Normandy peninsula, and this is all happening before the defeat of the Veneti at sea has happened, or at least, news hasn't reached them yet, and the locals are rising up in rebellion to join the Veneti (I think this underlines how serious the threat was to the Romans). Some of the locals even murdered those of their town councillors who opposed joining the rebellion.

They're gathered under the lead of a commander named Viridovix, and they raise an army and approach Sabinus' camp, 2 miles away. They start marching out their troops in battle formation every day to try to challenge the Romans to a fight.

Sabinus however, following the classic Roman strategy, has fortified his camp on high ground, with a long slope in front of them, about a mile long.

And after a few days of this Sabinus’ men start to say, come on, we can take them, lead us out—however Sabinus refuses. And the enemy even marches all the way up to the walls of his camp and throw insults at him.

And this goes on long enough that the Roman soldiers themselves start to accuse Sabinus of cowardice.

Caesar describes what happens next, and it makes you think, this was all part of Sabinus’ plan:

When this impression of timidity had been confirmed, he chose out a fit man and a cunning, one of the Gauls whom he had with him as auxiliaries. He induced him by great rewards and promises to go over to the enemy, and instructed him in what he would have done. When the pretended deserter had reached the enemy, he set before them the timidity of the Romans, explained to them how Caesar himself was in straits and hard pressed by the Veneti, and told them that no later than next night Sabinus was to lead his army secretly out of his camp and to set out to the assistance of Caesar.

Upon hearing this, they all cried with one consent that the chance of successful achievement should not be lost — that they should march upon the camp. Many considerations encouraged the Gauls to this course: the hesitation of Sabinus during the previous days, the confirmation given by the deserter, the lack of victuals (for which they had made too careless a provision), the hope inspired by the Venetian war, and the general readiness of men to believe what they wish. With these thoughts to spur them on, they would not allow [their leader] Viridovix and the rest of the leaders to leave the council until they had their permission to take up arms and press on to the camp. Rejoicing at the permission given as though at a victory assured, they collected faggots and brushwood to fill up the trenches of the Romans and marched on the camp.

So Sabinus began with a modest advantage, right, he's got the high ground, he's got superior soldiers, but partly due to the extreme asymmetric advantage the Romans have in logistics (he's got all the provisions he needs really, and the Gauls typically just don't have that kind of infrastructure worked out to supply a standing army for a long time in a single place, with all the hungry men and horses and pack animals... time is almost always on the Romans' side in this war) , he waits to turn his modest advantage into a major advantage, to trick the the Gauls into committing to battle on very unfavorable terms.

And as Caesar mentions, to reach the Roman camp the Gauls have to hike a mile uphill.

And that's exactly what they do, they charge up the hill at a dead run, thinking this will give them the element of suddenness and surprise... but once they get to the top they're pretty exhausted, because they are also carrying bundles of sticks and logs and bushes to fill up the Roman trenches and assail the walls.

And that's exactly when Sabinus strikes, he sallies out of two gates at once, with determined, enthusiastic, well rested troops.

You can guess what happens next:

The order was executed with the advantage of ground; the enemy were inexperienced and fatigued, the Romans courageous and schooled by previous engagements. The result was that without standing even one of our attacks the Gauls immediately turned and ran. Hampered as they were, our troops pursued them with strength unimpaired and slew a great number of them; the rest our cavalry chased and caught, and left but a few, who had got away from the rout. So it chanced that in the same hour Sabinus learnt of the naval battle, and Caesar of Sabinus' victory; and all the states at once surrendered to Sabinus. For while the temper of the Gauls is eager and ready to undertake a campaign, their purpose is feeble and in no way steadfast to endure disasters.

So again, if you take one lesson from this whole series, it's do everything you can to fight your enemies on your own terms, on ground and conditions that favors you. Think of the Roman logistical system backing Sabinus up, think of his selection of his site, think of his choice to wait...

You can be devastating that way even with inferior numbers.

Lessons in Leadership #2: The Story of Publius Crassus

Alright, the final case study is young Publius Crassus, son of Caesar's patron Marcus Crassus.

He's headed for Aquitainia, the southwest of France—remember Caesar sent him there at the outset of the war with the Veneti, with the ostensible mission of preventing the Aquitanians from sending any aid to the Veneti. So it's a sort of pre-emptive strike, and kind of makes sense given that the Aquitainians are a Gallic people who live just further down along the coast.

So Crassus does his duty, and crosses the Garonne river. He's immediately attacked by a powerful nation called the Sotiates, and after a fierce battle he defeats them.

Then he attacks them at one of the strongholds they've retreated to. He gets out the siege sheds, the vines, and starts building his siege towers... Caesar points out here that the Aquitainians put up a particularly strong fight because they are world experts at this art of tunnelling underground, since there are a lot of copper mines in this region

But Crassus and the Romans manage to fight them off, collapse tunnels, whatever it took.

And they finally surrender... so it would seem. But then this happens:

Their request was granted, and they proceeded to deliver up their arms as ordered. Then, while the attention of all our troops was engaged upon that business, Adiatunnus, the commander-in‑chief [of the Sotiates], took action from another quarter of the town with six hundred devotees, whom they call soldurii. [this is very interesting] The rule of these men is that in life they enjoy all benefits with the comrades to whose friendship they have committed themselves, while if any violent fate befalls their fellows, they either endure the same misfortune along with them or take their own lives; and no one yet in the memory of man has been found to refuse death, after the slaughter of the comrade to whose friendship he had devoted himself5. With these men Adiatunnus tried to make a sortie; but a shout was raised on that side of the entrenchment, the troops ran to arms, and a sharp engagement was fought there. Adiatunnus was driven back into the town; but, for all that, he begged and obtained from Crassus the same terms of surrender as at first.

So Crassus is remarkably merciful in the end there.

But it's not over, and there are other nations of Aquitania raising up armies to crush the Romans. Again, Crassus is very close to Spain, and here's what he's up against:

At this juncture the natives, alarmed by the information that a town fortified alike by natural position and by the hand of man had been carried within a few days of his arrival, began to send deputies about in every direction, to conspire together, to deliver hostages to each other, and to make ready a force. They even sent deputies to those states of Nearer Spain which border on Aquitania, inviting succours and leaders from thence. Upon their arrival they attempted the campaign with great prestige and a great host of men. And as their leaders for the same they selected men who had served for the whole period with Quintus Sertorius and were believed to be past masters of war. These leaders, in Roman fashion, set to work to take up positions, to entrench a camp, and to cut off our supplies.

Sertorius, you will remember if you've listened to his life, was one of the toughest foes Romans faced in this century, he was known for training his men particularly well.

So these guys are using a solid Roman strategy against the Romans, they end up walling themselves off in a fort, with very good supplies, and they are sending out into the countryside to cut off the Roman supply chains, to get time on their side.

So Crassus judges, he's got to attack quickly and force a battle - but Caesar takes the time to point out, Crassus also called a meeting of his war counsel to put the question before them, like a good lad, consulting the wise elders. And they agree with him. Do a battle, do it.

So, let's just say, long story short, Crassus attacks the Aquitainian fort, and he does it by a frontal assault, and it's a hard slog, but then he has his cavalry ride around unseen to the back and they scope out a weakly defended point behind the defenders, and they manage to take the camp from behind, and before the defenders know what's happening, their streets are flooded with Roman auxiliaries and the infantry at the front of the fort get their energies renewed, and overwhelm the city.

So, with that, Aquitainia is pacified. Great work, Young Crassus!

The Bigger Game…

Now, that episode of its own is an inspiring case study for young leaders entrusted with a difficult independent mission...

But I think one of the big reasons Caesar included it and gave Crassus so much air time in these commentaries is because of the bigger chess game Caesar is playing with the power politics situation in Rome.

See, after this campaign, Publius Crassus heads home to Rome, leading a couple of legions of Caesar's fighting men, precisely so that they can vote in the Consular elections for the consuls of the year 55.

This was part of the deal that Caesar struck with the other triumvirs Crassus and Pompey at the conference of Luca we mentioned earlier. The plan is, for Pompey and Crassus to get elected Consuls - and of course, this is in the days before mail in ballots.

So, he wants to send Crassus home with as much glory and honor as possible, to make all that very easy for him to do, and to catch some goodwill from Publius’ father Marcus, who's going to be very important in securing Caesar's interests in Rome in the coming years.

He uses his power as a writer, and his position as a general, to shore up his status as a politician by supporting his friends back home...

If all that's not 4D chess, I don't know what is. And it shows how masterful Caesar was at playing these two games at once.

Caesar, you might recall from the life of Crassus, also lent some of his auxiliary Gallic cavalry to join the Crassuses, father and son, on their grand, ill fated mission to Mesopotamia... which, let's not invite bad omens by recounting that story here. But just imagine for a moment, these Gauls going from fighting, arguably, their own countrymen in Aquitania... riding all the way to the desert steppes of northern Iraq.

Incredible.

Napoleon makes an interesting comment here reflecting on the successes of Caesar and Crassus and Sabinus too in this book:

Here's what he says:

Brittany, that large and difficult province, submitted without making efforts in proportion to its strength. The same applies to Aquitaine and Lower Normandy. [Very interesting - and Caesar does remind us in the book that Aquitania comprised pretty much a third of the entirety of Gaul, so Napoleon has a good point here - Crassus only had a little more than one legion of troops, though he had a particularly strong Cavalry attachment too. But here's the point Napoleon wants to draw out about the apparently lackluster performance from the Gauls of these various regions] This [Napoleon says] is due to causes which cannot be precisely determined, but it is easy to see that the main reason lay in the spirit of isolation and local loyalty which characterized the peoples of Gaul. At this time they had no national or even regional spirit; their loyalty was at the level of the town. This is the same spirit which has since forged the fetters of Italy. Nothing is more opposed to a national spirit, to general ideas of liberty, than the private spirit of family or village. Because of this fragmentation, it also followed that the Gauls had no trained standing army, therefore no knowledge of military science. If Caesar’s glory depended solely on his conquest of Gaul, it would be in doubt. Any nation which lost sight of the importance of a standing army ever-ready for action, and which relied on mass levies or militias, would suffer the same fate as Gaul...

— from Napoleon's Commentaries on the Wars of Julius Caesar: A New English Translation (link)

And of course, we've only just begun to get a glimpse of the deeds that build Caesar his glory.

Well on that point by Napoleon, once again, you see the wisdom of a guy like Alexander Hamilton (another avid reader of Caesar's commentaries), insisting that the newly founded nation of the United States have a strong standing army, rather than these disparate local militias a lot of the decentralization-favoring Republicans like Jefferson preferred. Hamilton was a man Talleyrand considered even greater and more brilliant than Napoleon (Talleyrand knew both of them personally).

Meanwhile, to close the book Caesar goes off to Northeast Gaul to give another couple of small rowdy tribes the Caesar treatment for rebels, he chops down huge swaths of their forests...and they scurry away after only a paragraph or two.

And with that, the campaigns of the year 56 are over.

That's all for today, if you enjoyed this, leave us a good review, tell a friend, or, better yet, try to learn these deeds of Caesar inside and out, and share the lessons you draw from them with a friend you think might need some advice or encouragement.

Thanks for listening. Stay Strong, Stay Ancient. This is Alex Petkas, until next time.

I'm informed by Google maps that there are some very nice ski areas around there now…

We will return to this issue when we discuss Caesar reading De Rerum Natura on his campaign

We met with an institution like this in Spain already, way back in the life of Sertorius, the greatest Roman Rebel, when Sertorius actually had his own group of these soldurii types, totally devoted, to the death, to their commander.

Ooh! Looking forward to listening to this one! 💚 🥃