This is the beginning of a new series on Caesar’s masterwork of psychology, strategy, and propaganda: On the Gallic Wars (De Bello Gallico). It’s a world-history making story (the conquest of what’s now modern France), told by a world-history making storyteller.

Caesar entered Gaul as a mere politician. He returned 9 years later as a conqueror - and an enemy of the state. He tells how it all happened with his own pen.

I’m having a blast revisiting this classic, and I think you will too.

This episode is sponsored by Ancient Language Institute. If you want to be like Caesar, you should learn an ancient language (Caesar knew Greek in addition to his native Latin). The Ancient Language Institute will help you do just that. Registration is now open (till August 10th) for their Fall term where you can take advanced classes in Latin, Ancient Greek, Biblical Hebrew, and Old English.

Now You Listen Here:

Stay Ancient,

Alex

Transcript

Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur. Hi omnes lingua, institutis, legibus inter se differunt.

Gaul is a whole divided into three parts, one of which is inhabited by the Belgae, another by the Aquitani, and a third by a people called in their own tongue Celtae, in the Latin Galli. All these are different one from another in language, institutions, and laws.

— Caesar, “Gallic War” (Book 1, Chapter 1)1

That is the pretty famous beginning of one of the most influential books in history, written by one of the most influential men ever. It's Julius Caesar's De Bello Gallico, On the Gallic Wars.

Famous first lines among other reasons because—funny enough—it's the first real Latin that generations of European schoolboys would encounter in their studies...

But this is no schoolboy's book.

Like countless other great commanders, Napoleon kept a copy of this book with him when he went on campaigns and he wrote a whole commentary on it when he was at the end of his life in exile on St Helena.

In On the Gallic Wars, De bello Gallico, Caesar catalogs the nine year campaign he fought to conquer ALL of what is now modern France, modern Belgium, some of Switzerland, and a little more too. He spent 9 years away from Rome—IN HIS PRIME, politically speaking— and he never entered the city or Italy proper for that time, which is pretty incredible.

But this was the campaign that made his career, and forged the foundation of modern France... and, you could even argue, the whole of modern Europe. It was not inevitable that the Romans should rule these lands, by any stretch.

I'm Alex Petkas, you are listening to the Cost of Glory, where it is our mission to retell the lives, deeds, and characters, of the greatest Greek and Roman heroes. This is part 1 of 8 of the Gallic Campaigns of Julius Caesar. This is also part of a larger arc we're doing called Visions of Caesar, telling the lives and stories of all the men who knew, loved, supported, hated, and killed Caesar. We've already done Crassus and Pompey, full bio of Caesar himself coming soon.

The Cost of Glory is produced in collaboration with Infinite Media.

Now, I want to jump into it pretty quickly here. I'm going to give you my highlights of this book, share with you what I think are the most important stories, and the most useful lessons.

Why did Caesar write The Gallic Wars?

But it's useful to consider for a moment—why did Caesar write this text (this 8 book masterwork, [of which] we're going to do book 1 in this episode)?

Well, for many reasons that we'll discuss along the way. But I think the #1 reason, that scholars surprisingly don’t talk about a whole lot is this:

Caesar wrote De Bello Gallico to educate his future talent pool. He wanted to show Romans of ambition and talent, the kind of man he was, and the sort of men he attracted to himself, the sort of commanders and engineers and other leaders he wanted, what skills and expertise he expected of them, and also, the kind of qualities the regular soldiers were expected to have, if they wanted to fight under CAESAR.

And I think it's interesting, he does point out many mistakes that he, and his officers, and his soldiers make. He's genuinely trying to teach you.

I think that this #1 reason—that here you have one of history's greatest leaders and strategists opening up his playbook, to share with you his secrets—explains to you both why this text was so popular and influential for so many great conquerors, and leaders, and artists and explains what you can get out of it2.

The Venture Capitalist Don Valentine used to say that the skill of storytelling is of incalculable value (I paraphrase) because capital follows storytelling3. And Caesar was very good at raising capital from men like Crassus (see the episodes we did on him, episodes 72 to 74). I think you can start to see why [after] reading this book.

Well, let's get to it.

The Territory of the Gauls

Now, The first thing that strikes you about this book when you crack it open, is how vast and complicated the territory he's looking at is.

Here's how it begins (and I'm reading from the Public Domain Loeb translation of Edwards by the way, which I occasionally modify for Clarity. I also really like, if you want to buy a physical book version, the Landmark edition, many notes maps explanatory essays, it's great, and I'll be referring to it often for this series, alongside the Napoleon commentary).

Ok here we go, the vast complicated territory of Gaul4:

Gaul is a whole divided into three parts, one of which is inhabited by the Belgae, [these people live in what's Belgium today, named after them] another [part is inhabited by] by the Aquitani [this is Aquitaine which is southwest France], and a third [here we go] by a people called in their own tongue Celtae, in our Latin language Galli. All these are different one from another in language, institutions, and laws. The Galli [I'll call them Gauls from here on out] are separated from the Aquitani by the river Garonne, from the Belgae by the Marne and the Seine. Of all these peoples the Belgae are the most courageous, because they are farthest removed from the culture and civilization of the [Roman] Province, and least often visited by merchants introducing the commodities that make for effeminacy [and isn't he right on that point...]; and also because they are nearest to the Germans dwelling beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually at war. [We'll meet these guys, the Belgae, in book 2, they live roughly in Belgium as you can guess from their name. But here he's going to turn to the Tribe in question in this book]. For this [same] cause the Helvetii also excel the rest of the Gauls in valour, because they are struggling in almost daily fights with the Germans, either endeavouring to keep them out of Gallic territory or waging an aggressive warfare into German territory.

So Caesar is standing, let's imagine, in the Roman Province of Transalpine Gaul, he'll generally just call it Provincia, the Province, in these texts...

The Romans already directly rule a pretty decent sized chunk of what's now France, let's say a tenth, in the south-east corner, closest to Italy. It's basically a strip along the coastline that goes all the way to Spain, but also toward the East, it juts upward along the Rhone valley all the way to Vienne, about 200 miles inland. And this region more or less is now called, Provence, from that original name, Provincia.

Caesar is right now—the year is 58 BC—he's the governor of Transalpine Gaul, as well as Cisalpine Gaul (which is what the Romans called Northern Italy north of the Po river, more or less the part of Modern Italy that does NOT stick out into the Mediterranean), and there are a lot of tamer Gallic peoples in both of these parts.

Caesar’s Mindset at this time

And Caesar has an extraordinary 5 year command of these two provinces, (and also Illyricum, which is Slovenia and Croatia more or less). Listen to the lives of Pompey and Crassus we did already, for some of the back story of how he got that command.

Now…you might know the story of how Caesar, once when he was around 33—on a tour of duty, in Spain, the story goes—He saw a statue of Alexander the Great, and he burst into tears. And his friends asked him, Caesar what's the matter? And he responded “Do you not think, it is matter for sorrow that while Alexander, at my age, was already king of so many peoples, I have as yet achieved no brilliant success?”5

So Caesar from early on in his career, knew the Historical Figure he was trying to emulate, or even outdo. By this point I suggest you might want to figure that out for yourself too if you haven't yet.

And there's another story to this point... when he was crossing the Alps around this time, he was in some podunk town and one of his buddies says to him, “Ah Caesar, I bet these silly little natives have their own struggles for supremacy within their towns like we Romans strive for the highest office of consulship in our city, but oh, how pathetic”... and he laughs...and Caesar looks him, dead serious, and he says, “I would rather be the first man in this town than the second man in Rome.”6

So those are the stakes for Caesar. He's now 42, and he's looking at this vast territory... and he's been consul already (the previous year, in 59). He's a great politician yes, but he's thinking, he's got 5 years to prove himself a great commander...worthy of the company of Alexander the Great.

And 5 years is a pretty short period to take over all of France you might say. Especially considering, the Romans have a really checkered military record with the Gauls. It was Gauls who torched the city of Rome itself around 390 BC, it was Gauls who, after many other signal victories against the Romans, also annihilated a gigantic Roman army at Arausio in 105 BC, and invaded Italy itself. This is all very much living memory for a lot of the older Romans at this time—you'll recall this if you've listened to our Life of Marius and Sertorius.

Bottom line is these people are TOUGH, and the Romans know it. They're tall and scary, but also wild and crafty, extremely warlike, even the softer of them.

But let's go on…

So now he's introduced some of the main tribal constituencies he's going to deal with through the book.

But last of all in that paragraph there he mentioned the Helvetii, who are a very warlike tribe of Gauls. They live in the western part of modern Switzerland, Helvetia... which does indeed border the Rhine.

These people are the focus of the first half of book 1.

The Helvetii

He goes on to tell us about the Helvetians a little more, in particular this one noble Helvetian, and this is a little bit of a back story:

“Among the Helvetians the noblest man by far and the most wealthy was Orgetorix. In the consulship of Marcus Messalla and Marcus Piso [that's 61 BC, so 3 years earlier - the Romans name the years after the consuls who serve in them... so in 61] [Orgetorix's] desire for the kingship led him to form a conspiracy of the nobility, and he persuaded the community to march out of their territory in full force, urging that as they excelled all in valour it was easy enough to secure the sovereignty of all Gaul. In this he persuaded them the more easily, because the Helvetii are closely confined by the nature of their territory.”

And Caesar goes on and explains very carefully here. The Helvetians live on this plain on the north side of Lac Leman, and their territory is bounded by the Jura mountains to the north and West, the Lake, Lac Leman, and the Rhone river to the south, and then by the Rhine and the Germans to the East. And according to Caesar they're hankering for what you might call Lebensraum, more "Room to Live".

So Orgetorix wants to use this plan of expansionism... to elevate himself to a position of King. The Gauls are all at this point ruled by aristocratic councils, so they're oligarchies, but they have this not too distant memory of when they were ruled by Kings and guys like Orgetorix in this story are always scheming to restore the kingship and put themselves on the throne.

Now Orgetorix on the side here launches this secret conspiracy, and he secretly approaches a couple of other Nobles—one in particular is a man named Dumnorix, he's a guy to keep your eye on.

(That Rix suffix by the way is the celtic equivalent of the Latin Rex—King. So many of these gallic nobles even have "king" built into their names, so you know this is all pretty understandable).

Well Here's Caesar:

“Orgetorix likewise persuaded Dumnorix, of the Aedui [this is another key tribe], [Dumnorix the] brother of Diviciacus, who that time held the chieftaincy of the state of the Aedui and was a great favourite with the common people; Orgetorix persuaded Dumnorix to a like endeavour, and gave him his own daughter in marriage. He convinced [Dumnorix and the other nobles in on the conspiracy] that it was easy enough to accomplish such endeavours, because he himself (so he said) was about to secure the sovereignty of his own state.”

The Aedui are actually important Roman Allies, they live on the other side of the Rhone, in central france. More on them later.

But so, unfortunately for Orgetorix, his plot to make himself King is discovered, and the rival nobles put him on trial in chains for, basically, treason—and if he's guilty the punishment for aiming at kingship is to be burned alive. But Orgetorix manages to bring a lot of his thugs into the trial and he stages an escape, but then afterwards he apparently commits suicide.

However, he's started a fire, and the Helvetians are convinced they need that Lebensraum, and they are up for an adventure.

And here's where Caesar gets excited. Because the Romans don’t believe in unprovoked aggressive wars of conquest (in theory at least). There has to be some plausible danger a governor is addressing in order to engage in a campaign.

So here's what the Helvetii do:

“When at length they deemed that they were prepared for that purpose, they set fire to all their strongholds, in number about twelve; their villages, in number about four hundred, and the rest of their private buildings; [they are burning their whole state, amazing... and what's more] they burnt up all their grain save that which they were to carry with them, to the intent that by removing all hope of returning homeward they might prove the readier to undergo any perils; and they commanded every man to take for himself from home a three months' provision of victuals. They persuaded their neighbours, the Rauraci, the Tulingi, and the Latobrigi, to adopt the same plan, burn up their strongholds and villages, and march out with them.”

So where are they planning to go exactly? Well Caesar suggests later on it's mainly just a nice plot of land near the Atlantic coast. But yet, here, he frames this expedition as the Helvetians scheming to take over all of Gaul, since they believe themselves to be the most warlike of all. Well, that would clearly be a plausible threat to Roman interests...

So he may well be exaggerating here...

BUT! either way, he's actually got a pretty strong case that this is a problem he needs to deal with as governor because, he explains, the route they wanted to take was south—through the Roman Province—going around the southern foot Jura mountains. (This is also the territory of the Allobroges who are Gauls but they are are Roman allies living in the Roman province, their principle city is Genava, which is modern Geneva.)

So Caesar finds this all out through his informers, and he decides, hey, these Helvetians are going to rob and plunder as they make their way through the Province, so they've got to be stopped. The Helvetians conveniently set out in March of 58, which is when Caesar is just beginning his term as governor.

So Here's what he does—And you'll note here that he usually speaks about himself in the 3rd person, this gives him an air of objectivity7:

“When Caesar was informed that they were endeavouring to march through the Roman Province, he made speed to leave Rome, and hastening to Transalpine Gaul by as rapid stages as possible, he arrived near Geneva. From the whole Province he requisitioned the largest possible number of troops (though there was in Transalpine Gaul no more than a single legion), and ordered the bridge at Geneva to be broken down…”

So he breaks down the bridge over the Rhone at Geneva, to keep the Helvetians from crossing... and note here he's only got 1 legion, which is a little less than 5,000 men. Military history fans take note, this is the famous 10th legion, which became one of his most trusted elite forces, they fought at the battle of Pharsalus.

“[now] When the Helvetii learned of his coming, they sent as deputies to him the noblest men of the state... with instructions to say that their purpose was to march through the Province without any mischief, because they had no other route; and they asked that they might be given leave to do so by Caesar's good will. Caesar, however, Remembering that the consul Lucius Cassius had been slain, and his army routed and forced to walk under the yoke, by the Helvetii [by these very Helvetii! - that major Roman upset was in 107 BC, which here is a great opportunity for Caesar to remind his Roman readers that these people are DANGEROUS], Caesar considered that no concession should be made; nor did he believe that men of unfriendly disposition, if granted an opportunity of marching through the Province, would refrain from outrage and mischief. [that's really key, he's underlining the reasonable threat]. However, [here's what he does] to gain an interval for the assembly of the troops he had levied [i.e. beyond the single 10th legion he's got], he replied to the deputies [of the Helvetii] that he would take a space of time for consideration; if they wished for anything, they were to return on the 13th of April.”

So he's buying some time. The Helvetii he notes later on, are moving their entire nation, more than 300k people, including at least 90,000 fighting men and he's only got 5,000.

Now check this out, this is pretty amazing what he does next (again note Caesar's talking in the 3rd person here):

“In the meanwhile he used the legion which he had with him, and the troops which had concentrated from the Province, to construct a continuous wall, sixteen feet high, and a trench, from the Lake of Geneva (Lac Leman), which flows into the river Rhone, to the Jura range... a distance of nineteen miles”

If you look at a map this basically cuts them off and makes it so their only choice is to march through the Jura mountains, which they REALLY don't want to do...

Napoleon’s comments on Caesar’s strategy

And many scholars doubt that Caesar could have pulled off this incredible fortification work so quickly. But I think for the doubters, it's worth going behind the scenes for just a second here with Napoleon himself to get into the mind of a great general.

And this is a quote from Napoleon's commentary on Caesar's Gallic Wars:

“The ordinary field fortifications of the Romans consisted of a V-shaped ditch 12ft wide by 9ft deep: with the spoil [that is the dirt they dug out] they erected a bank 4ft high and 12ft wide, on which they raised a parapet 4ft high made of stakes driven 2ft into the ground; which meant that the crest of the parapet was 17ft higher than the bottom of the ditch. A 2-yard running section of this fortification, requiring 324 cubic feet of excavation (12 cubic yards), could be completed by one man in thirty-two hours, or three days of work, or by twelve men in two or three hours. The legion which did the work could have completed its 14 miles of defences [16 Roman miles is 14 modern miles], involving 168,000 cubic yards of excavation, in 120 hours, or ten to fifteen days’ work.”

Well, I think there's a lesson there. If you're wondering if you can do something hard, sit down and do the math. I think Caesar did, and I think he built the thing.

Caesar stops the Helvetii

And here's what it allowed him to do (and we're back to Caesar's words now):

“This work completed, Caesar posted separate garrisons, in entrenched forts, in order that he might more easily be able to stop any attempt of the enemy to cross against his wish. When the day which he had appointed with the deputies arrived, and the deputies returned to him, he said that, following the custom and precedent of the Roman people [note how he frames it there], he could not grant anyone a passage through the Province; and he made it plain that he would stop any attempt to force the passage. Disappointed of this hope, the Helvetii attempted, sometimes by day, more often by night, to break through, either by joining boats together and making a number of rafts, or by fording the Rhone where the depth of the stream was shallowest. But they were checked by the line of the entrenchment and, as the troops concentrated rapidly, by missiles, and so abandoned the attempt.”

So now, the Helvetians give up... and they say, well, we've got to cross the Jura mountains. And the Jura are high and forbidding but they're not ALPS high, you know, all the peaks are below treeline—they are big hills basically. HOWEVER... the Jura, and especially the Plains on the other side of Jura, to the north, are the territory of another great Gallic confederacy called The Sequani. Well, the Helvetians reach out to their friend Dumnorix of the Aedui (remember him from earlier), who they know also has great influence among the Sequani, and they ask him to intercede on their behalf, and he works out a deal. The Sequani say OK, they exchange hostages, and the Helvetii get to moving their nation slowly through the Jura.

At this point Caesar has a problem. The Helvetii are now safely going from outside the Roman province, through a route even further outside the Roman province (the territory of the Sequani), to a destination outside the Roman province (the territory of the Santones, near the Atlantic). But Caesar here in the text makes the case that, well, the Helvetii are going to end up in a spot close enough to to Roman interests in the Province that they were a reasonable threat. And so, he's got to stop these Helvetians stirring up trouble in the neighborhood.

It's a bit of a stretch to be honest.

Caesar’s Bold Move

But this decision leads Caesar to make a fateful move.

He kind of tosses it in there very nonchalantly (but hey, it's also notable that he doesn’t hide the fact...)

He says, “Caesar led his army into the territory of the Allobroges, and from there into the territory of the Segusiavi. [This is the nearest people outside the Province and across the Rhone].”

So he's just taken a step that will come back to haunt him (and he'll take this step many times actually)— he's crossed WITH AN ARMY outside of the boundary of his own allotted province.

You're supposed to get authorization from the Senate to do something that. So this is technically illegal.

We'll get to the ramifications of that, which are BIG, later (and you already have a concept of this if you've listened to the life of Pompey...you gotta imagine Caesar's enemy Cato the Younger for one thing is paying very close attention to these rules).

But you know, I think that's a lesson, if you're going to break the rules, it's often good to tell people about it and not hide the fact (the Senate is going to read the report here remember). But you want to do what Caesar does here, and sandwich that fact in between some very good reasons for your doing so. I mentioned the first... the generic threat to Roman interests from having a warlike tribe settle near-ish to the province... but lucky for Caesar, the Helvetians give him [and, of course, THE ROMAN PEOPLE as he says] great reason to be alarmed.

See they get through the land of the Sequani, and they get into the territory of the Aedui, and they start ravaging farms, plundering property. Now the Aedui, remember, are Roman allies (even though they're not in the province), and oh, by the way, as he notes, the Allobroges (who are also Roman allies) have some villages in this area, these guys are getting plundered too, and so all these Gauls, he says, they come and complain to Caesar.

And this was a key mistake by the Helvetians... and well, you could say, hey, they had no choice they're running out of food... but this is why as they say amateurs talk strategy, professionals talk logistics... because since they failed to bring enough supplies, or arrange to get them peacefully, well they had to take what they could get wherever they could get it...but this is going to really come and bite the Helvetians hard.

So, to summarize, Caesar blitzes back to northern Italy, and he brings back with him 5 whole new legions (so some 25,000 men, he's got a real army now).

Caesar strikes…

And thanks to his incredible, famous, speed... he catches the Helvetian folk by surprise right as they are making their way across another River, the Saône ("Sōne"), and just as they've brought 3/4 of their forces across (which took them a whopping 20 days, such a huge and chaotic mass of people and wagons and women and children...)

Caesar strikes as they are crossing in the night, and in the chaos the Roman slaughter a huge number of these Gauls. It's devastating.

And Caesar makes an interesting comment here:

“These people were from the tribe that is called Tigurini; for the whole Helvetian nation is divided into four cantons. In the recollection of the last generation it was this tribe [this canton] that had marched out alone from its homeland, and had slain the consul Lucius Cassius and sent his army under the yoke [that was the disaster he mentioned earlier from 107 BC]. And so, whether by accident or by the purpose of the immortal gods, the section of the Helvetian state which had brought so signal a calamity upon the Roman people was the first to pay the penalty in full.”

And Caesar usually doesn't go in for this kind of thing, but since he's got the opportunity he takes it, he knows that kind of "divine retribution" line is going to play very well among the Roman plebs when the messengers relay this story in the Forum—it's very good propaganda.

Caesar’s encounter with Divico

Now here, you might be tempted to feel sorry for these poor Helvetians, especially the Tigurini, minding their own business, trying to have a good Völkerwanderung8 as it were, and here the mean Romans come along and slay them (and I get that, yes...)

However!

Caesar explains what happens next, and this next part is some really good storytelling:

He builds a bridge across the Saône, and crosses his army over in a single day, which wows the natives with Roman technological mastery, and then they send him a DELEGATION.

And who would they choose but a man named DIVICO, who—SO IT HAPPENED—was the VERY GENERAL who had led the army that had destroyed the consul Lucius Cassius nearly 50 years earlier.

He must have been a really old man, but he's still got some fire.

Here's Caesar describing the encounter:

“[Divico] treated with Caesar as follows: If the Roman people would make peace with the Helvetii, they would go whither and abide where Caesar should determine and desire; if on the other hand he should continue to visit them with war, he was advised to remember the earlier disaster of the Roman people and the ancient valour of the Helvetii. Caesar had attacked one single tribe unawares, when those who had crossed the river could not bear assistance to their fellows; but that event must not induce him to rate his own valour highly or to despise them. The Helvetii had learnt from their parents and ancestors to fight their battles with courage, not with cunning nor reliance upon stratagem. Caesar should therefore take care lest the place of their conference derive renown or perpetuate remembrance by a disaster to the Roman people and the destruction of an army.”

Uh oh... fighting words...

“To these remarks Caesar replied as follows: As he remembered well the events to which the Helvetian deputies referred, he had therefore the less need to hesitate; and his indignation was the more vehement in proportion as the Roman people had not deserved [that earlier] misfortune... And even if he were willing to forget an old affront, could he banish the memory of recent outrages — their attempts to march by force against his will through the Province, their ill‑treatment of the Aedui, the Ambarri, the Allobroges? [so he's pointing to that earlier assault on his fortifications back at the Rhine - hey, they started it you could argue...] Their insolent boast of their own victory, their surprise that their outrages had gone on so long with impunity, pointed to the same conclusion; for [listen to this] it was the custom of the immortal gods to grant a temporary prosperity and a longer impunity to make men whom they purposed to punish for their crime smart all the more severely from a [later] change of fortune.

Yet, for all this, Caesar would make peace with the Helvetii, if they would offer him hostages to show him that they would perform their promises, and if they would give satisfaction to the Aedui in respect of the outrages inflicted on them and their allies, and likewise to the Allobroges.”

So Caesar here is more or less asking them to surrender and submit.

Ah but listen to how the old man comes back [at Caesar]:

“It was the ancestral practice and the regular custom of the Helvetii to receive, not to offer, hostages; the Roman people was witness thereof. With this reply he departed.”

It is not looking good for the Helvetians—but, you know, in all fairness they do massively outnumber the Romans.

So, long story short, Caesar starts pursuing the Helvetians as they march further from the River, and there are some skirmishes, in one of the skirmishes the Romans' cavalry loses in a little engagement, and the Helvetians get really confident (and it's important to note, throughout this campaign, the Roman cavalry is almost entirely comprised of FOREIGN Auxiliaries, namely, local Gallic allies who have sent contingents of knights along with their horses)...

But as he's going on harassing the Helvetians, Caesar runs into another problem.

Caesar deals with Dumnorix

He's asked the Aedui (Roman allies remember) to support the war effort by providing food supplies, and the Romans are getting very low on food, and the Aedui keep coming up with excuses... so Caesar smells something fishy going on. And he eventually pulls some of the Aedui chief leaders into a council, including the vergobret of the Aedui, which is their chief annually elected Magistrate - this is an office that is controlled by the famous priestly class of Gauls, the Druids... more on these interesting people later...

Well, the vergobret, of the Aedui, his name is Liscus... after some cross examination by Caesar, Liscus breaks down and admits, there are powerful people among the Aedui sowing dissension and making it their goal to prevent the Romans from ever getting any supplies (the vergobret does not name any names)...

Caesar has his suspicions... so he dismisses everyone but Liscus the vergobret, and basically says: It's Dumnorix, isn't it, and Liscus confesses, yes, it's Dumnorix—that crafty Aeduan noble who was scheming with the Helvetii, and the Sequani.

And in fact, Caesar finds out, Dumnorix was the man responsible for this recent minor defeat of Caesar's Gallic auxiliary cavalry (that was on purpose, they threw the fight, it turns out).

But this presents him with another problem, and here's what's going on in Caesar's mind, and here's what he does about it (some more great storytelling here):

“Caesar deemed all this to be cause enough for him either to punish Dumnorix himself, or to command the state of the Aedui to do so. To all such procedure (however) there was one objection, the knowledge that Diviciacus, the brother of Dumnorix, showed the utmost zeal for the Roman people, the utmost goodwill towards Caesar himself, in loyalty, in justice, in prudence alike remarkable; for Caesar apprehended that the punishment of Dumnorix might offend the feelings of Diviciacus.”

So Diviciacus—Dumnorix' brother, he's one of the other Aeduan nobles, and Caesar actually keeps a number of these guys in his camp as, let's call them, advisors—Diviciacus is actually a Druid. More on the druids in later episodes...

So going on, he summons Diviciacus alone and he presents the facts before him. And Caesar's like, so, what should I do?9

“With many tears Diviciacus embraced Caesar, and began to beseech him not to pass too severe a judgment upon his brother. "I know," said he, "that the reports are true, and no one is more pained thereat than I, for at a time when I had very great influence in my own state and in the rest of Gaul, and he very little, by reason of his youth, he owed his rise to me; and now he is using his resources and his strength not only to the diminution of my influence, but almost to my destruction. For all that, I feel the force of brotherly love and public opinion. That is to say, if too severe a fate befalls him at your hands, no one, seeing that I hold this place in your friendship, will believe that it has been done without my consent; and this will turn against me the feelings of all Gaul." While he was making this petition at greater length, and with tears, Caesar took him by the hand and consoled him, bidding him to end his entreaty, and showing that his influence with Caesar was so great that Caesar excused the injury to Rome and the vexation felt by himself, in consideration for the goodwill and the entreaties of Diviciacus. Then he summoned Dumnorix to his quarters, and in the presence of his brother he pointed out what he had to blame in him; he set forth what he himself perceived, and the complaints of the state; he warned him to avoid all occasions of suspicion for the future, and said that he excused the past in consideration for his brother Diviciacus. He posted sentinels over Dumnorix, so as to know what he did and with whom he spoke.”

There's a great lesson for someone in power... Sometimes they say, what seems like malice is really incompetence... but then... very often indeed what seems like incompetence... is actually malice of one form or another. You gotta do some sleuthing to figure out what it is.

The Helvetians Attack

Well, pretty soon the war all comes to a head near this hill fort the Romans camp by, a place called Bibracte. It's in the territory of the Aedui (near modern day Autun).

And Basically what happens is, Caesar is starting to build a camp on this favorable site on a hill, the Helvetians launch a sudden mass attack.

Caesar quickly sets up his lines halfway up the hill (he's got his army 3 lines deep, with the new recruits in the back, you want to ease them into this war thing of course).

And the Helvetians are therefore at a disadvantage, because, it's a lot harder to charge uphill than downhill, and they've also got a little stream at their back which hampers their retreat... but they go ahead and give it all they've got, for, as Napoleon observes "They were a dauntless people".

They also, again, greatly outnumber the Romans.

And I'll read you a snapshot of the battle Caesar gives us. And just note here that

Caesar is going to make use of ALL the advantages he can (ALWAYS), terrain being one of the chief ones, we've already mentioned it, he's got the high ground…

…Roman engineering and technology is another (they have these spears called the Pilum, you'll see what they do)

And then, his personal presence is huge here too10.

Here's a passage from his description of the battle's beginning, the Battle of Bibracte:

“Caesar first had his own horse and then those of all others sent out of sight, thus to equalise the danger of all and to take away hope of flight. Then after a speech to encourage his troops he joined battle. The legionaries, from the upper ground, easily broke the mass formation of the enemy by a volley of javelins, and, when it was scattered, drew their swords and charged. The Gauls were greatly encumbered for the fight because several of their shields would be pierced and fastened together by a single javelin-cast [this is the roman Pilum]; and as the iron [from the Roman Pilum] became bent, they could not pluck it out [of their shields], nor fight handily with the left arm encumbered. Therefore many of them preferred, after continued shaking of the arm, to cast off the shield and so to fight bare-bodied. At length, worn out with wounds, they began to retreat, retiring towards a height about a mile away. [so here, they retreat across the stream, to a hill on the other side...] [The Gauls] gained the height; and as the Romans followed up, the Boii and Tulingi [other Helvetian tribes], who with some fifteen thousand men brought up the rear and formed the rearguard, turned from their march to attack the Romans on the exposed flank, and overlapped them. Noticing this, the Helvetii, who had retired to the height, began to press again and to renew the fight. The Romans turned their standards, and fought the battle in two directions: the first and second line to oppose the part of the enemy which had been defeated and driven off, the third to check the fresh assault.”

So those new recruits at the back get a chance to show their stuff on the field.

And in the end, after a very hard fight, the Romans finally drive the Helvetii back to their circled wagon camp. The fight lasts from noon till deep into the night, but finally the Romans capture the Helvetian camp and drive the enemy in flight.

And all the way up until that final fight at the Helvetian baggage camp Caesar says, “nobody saw a single enemy turn his back”.

Plutarch adds that in the night battle at the wagons, “Not only did the men themselves make a stand and fight, but also their wives and children defended themselves to the death and were cut to pieces with the men.”

A dauntless people...

They chase the Helvetii to a spot 4 days march away, and force them to surrender. And with that the Helvetian war was over.

In the wagon camp, Caesar found tablets in the Gallic language, using Greek script, which indicated how many people the Helvetians had left their homeland with.

“The whole migration was about 368,000. [And he counts about 92k who were capable of bearing arms, the rest will have been the old, the servants, and of course the women and children]. Of those who returned home a census was taken in accordance with Caesar's command, and the number was found to be 110,000.”

Probably many of those 250,000 odd who were lost ended up fleeing and taking residence in nearby Gallic towns, maybe returning home much later... but many tens of thousands died, and many others, to be sure, were taken as slaves by the soldiers, and kept or sold off in the slave markets.

Truly an epic disaster for the nation of the Helvetians.

The Terror of Ariovistus

Well, you might have thought that Caesar had accomplished all you could hope to in a single campaign season. And I think your average Roman commander would have agreed—time to build some forts, sharpen some swords.

But Caesar has a very refined sense for opportunities. And he only has 5 years, right? So no time to waste.

Well the very next thing that happens (as he recounts), emissaries come to him from the leaders of tribes all over Gaul, praising him and thanking him (of course) for taking care of the disruptive Helvetians.

And they bring another matter to his attention.

(It's interesting here by the way they actually ask his permission to go hold their own private tribal conclave, without him present—so they are implicitly acknowledging his authority here... and he says yes that's fine go ahead). Well the Gaulish nobles come back and they've agreed to present another VERY CONCERNING matter to the Roman general.

And it's his loyal friend Diviciacus the Druid who gets picked to deliver the news.

Some Germans have crossed the Rhine in recent years, about 15,000 of them. Diviciacus explains, it was actually the Sequani that called the Germans in as basically mercenaries, because they were warring with his own tribe, the Aedui.

But now the Sequani have found—to their dismay—these originally hired henchmen, the Germans, have quickly become their masters. The king of these German "allies" who has turned into their overlord, is a man named Ariovistus.

Ariovistus and his Germans defeated the Aedui in a big battle, and in the process killed many of the flowers of the Aeduan nobles, and he forced the Aedui (Roman allies remember) to submit hostages to him, as guarantees of their good behavior.

But then...Ariovistus managed to extort the Sequani into giving over some of their OWN nobles (and in particular the children of those nobles) as hostages as well. And now Ariovistus is planning to bring over even more Germans and gradually force the Sequani, and who knows, any and all other nearby Gallic nations, out of their homes.

And here Caesar reports the speech that Diviciacus makes (Diviciacus is speaking, but of course, Caesar is the one telling the story) - and it is a great characterization of this haughty German king Ariovistus, but we'll skip it because we're going to hear from Ariovistus himself shortly.

But so, as they're in this council, in front of all these Gallic nobles from various tribes... Diviciacus ends his speech about the terrors of Ariovistus by bursting into tears and begging for Caesar's help and intervention.

Here's how Caesar responds:

“Caesar noticed, however, that of all the company the Sequani alone did not act like the rest, but with head downcast stared sullenly upon the ground [So the Sequani are there too] Caesar asked them why they were acting thus. The Sequani made no reply, but continued in the same sullen silence. When repeated questioning could extract not a word from them, Diviciacus the Aeduan made further reply. ‘The lot of the Sequani,’ he said, ‘is more pitiable, more grievous than that of the rest, inasmuch as they alone dare not even in secret make complaint or entreat assistance, dreading the cruelty of Ariovistus as much in his absence as if he were present before them. The rest, for all their suffering, have still a chance of escape; but the Sequani, who have admitted Ariovistus within their borders, and whose towns are all in his power, must needs endure any and every torture.’”

So these Sequani nobles are worried, if Ariovistus hears about them complaining, their sons are going to suffer for it.

So here the way Caesar is presenting this, you know, he's not just picking sides in an internal battle between Gauls, right, he's got an opportunity here to be a champion of All The Gauls, against these even MORE barbarian Germans, maybe he can pick up another ally for THE ROMAN PEOPLE in the process.

And he explains to his readers, well, letting the ROMAN ALLY Aedui get pushed around, their nobles terrorized, hostages held under dire threat—this did not comport with the dignity of the Roman People did it? Furthermore:

“Caesar could see that the Germans were becoming gradually accustomed to cross over the Rhine, and that the arrival of a great host of them in Gaul was dangerous for the Roman people. Nor did he suppose that barbarians so fierce would stop short after seizing the whole of Gaul; but rather, like the Cimbri and Teutoni before them [he's harking back here to the great Cimbrian wars under Marius from 105-100 BC, not so long ago!], they would break forth into the Province, and push on thence into Italy, especially as there was but the Rhone to separate the Sequani from the Roman Province. All this, he felt, must be faced without a moment's delay. As for Ariovistus himself, he had assumed such airs, such arrogance, that he seemed insufferable.”

So you can see where this is going. But Caesar makes a lot of effort to start by taking a more conciliatory course. Here's what he does:

“Caesar resolved, therefore, to send deputies to Ariovistus to request that they choose some half‑way station between them for a parley, as it was his desire to discuss with him matters of state and of the highest importance to each of them. To the deputation Ariovistus made reply that if he had had need of any kind from Caesar, he would have come to him, and if Caesar desired anything of him, he ought to come to Ariovistus... And he found himself wondering... what business either Caesar or the Roman people might have in that Gaul which [ARIOVISTUS] had made his own by conquest in war.”

Well! This is getting very interesting indeed. So Caesar shoots back and he keeps playing the role of ‘I'm just trying to be reasonable here’. And I think we should give him some credit that this tactic was taken in earnest... but of course, he knew the kind of man he was dealing with.

And he introduces an interesting fact into the mix, listen to this:

“When this reply had been brought back to Caesar, he sent deputies again to Ariovistus with the following message: For as much as, after great kindness of treatment from Caesar himself and from the Roman people (for it was in Caesar's year of consulship that Ariovistus had been saluted as king and friend by the Senate), Ariovistus expressed his thanks to Caesar and the Roman people by reluctance to accept the invitation to come to a parley and by thinking it needless to say or learn anything as touching their mutual concerns, Caesar's demand of him was…”

So Apparently, and we don't know much else about this... but Ariovistus for some reason had actually approached the senate in the year before, 59, that's when Caesar was consul, and Caesar arranged for Ariovistus to be saluted as a king, you know, recognized as a regional player in Gaul, which is vague, but it's not nothing. And this is the attitude Ariovistus now takes with the Romans? So here's what Caesar demands:

“[Caesar demanded] first, that Ariovistus should not bring any further host of men across the Rhine into Gaul [so don't bring any more Germans across...]; second, that he should restore the hostages he held from the Aedui and grant the Sequani [the poor Sequani] the full freedom to restore to the Aedui with Ariovistus' full consent the hostages they held; further, that he should not annoy the Aedui by outrage nor make war upon them or their allies [So Caesar's taking pains to stress here for his readers, he's working on behalf of the Aedui, the Roman allies]. If Ariovistus did as requested, Caesar and the Roman people would maintain a lasting kindness and friendship towards him. If Caesar's request were not granted, then, [...]11, Caesar would not disregard the outrages suffered by the Aedui.”

Now listen to this:

“To this Ariovistus replied as follows: It was the right of war that conquerors dictated as they pleased to the conquered; and the Roman people also were accustomed to dictate to those whom they conquered, not according to the order of a third party, but according to their own choice. If he, for his part, did not ordain how the Roman people should exercise their own right, he ought not to be hindered by the Roman people in the enjoyment of his own right. [He's like, hey, I thought you guys were conquerors too, this is how we conquerors do things, isn't it?] The Aedui, having risked the fortune of war and having been overcome in a conflict of arms, had been made tributary to himself. Caesar was doing him [Ariovistus] a serious injury, for Caesar's advance was damaging his revenues. Ariovistus would not restore their hostages to the Aedui, nor [however] would he make war on them nor on their allies without cause, if they stood to their agreement and paid tribute yearly; if not, they would find it of no assistance whatever to be called "Brethren of the Roman people." As for Caesar's declaration that he would not disregard outrages suffered by the Aedui, no one had fought with Ariovistus save to his own destruction. Caesar might try the issue by force whenever he pleased: he would learn what invincible Germans, highly trained in arms, who in a period of fourteen years had never been beneath a roof, could accomplish by their valour.”

And I love that last jab...we Germans sleep under the stars unlike you pampered townsfolk. Unlike these pampered Gauls even.

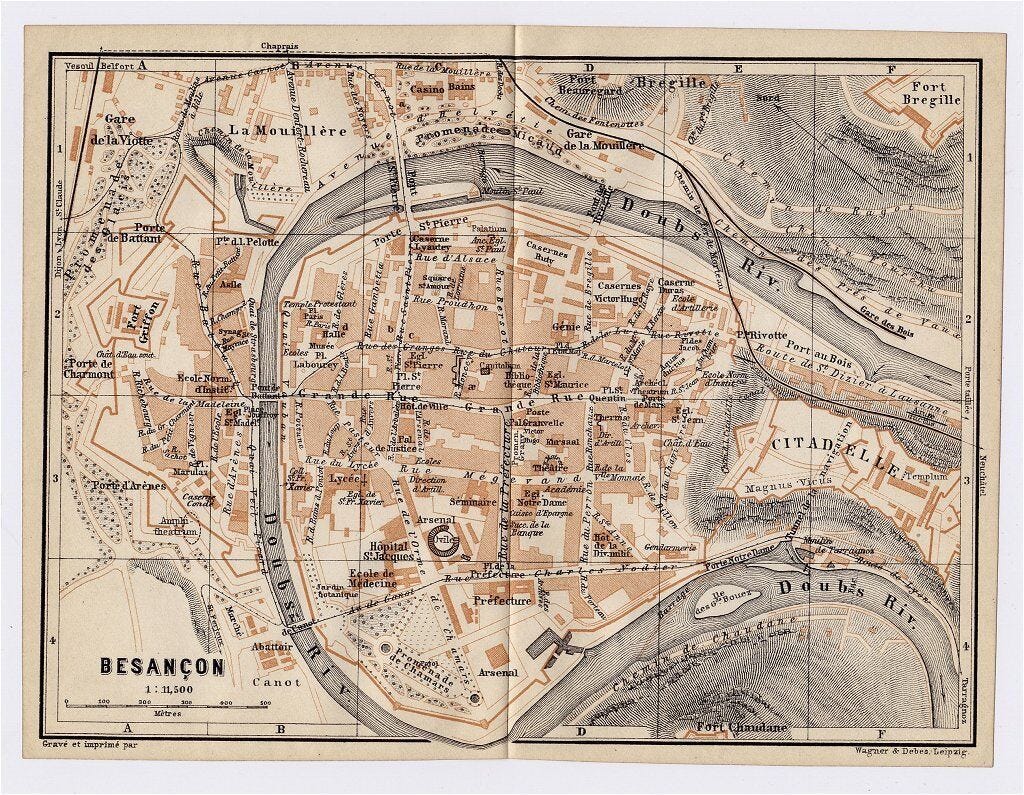

Well Caesar sees, it's time to snap into action. And he hears Ariovistus is on his way to try to occupy a town called Vesontio, modern Besançon, which is in the territory of the Sequani, and as he remarks, it's an amazingly good place to put a city. He says

“The Doubs river practically surrounds the whole town in a circle such that it looks as if it had been drafted by a compass, and the remainder of the circumference, a length of only about 1600 feet, that the river does not cover, is occupied by a towering hill, shaped so that the lower slopes on either side touch the river”.

And if you look at Besançon on a map, you'll see what he's talking about.

So Caesar blitzes to Vesontio, modern Besançon, and occupies it before Ariovistus can get there.

But! When he gets there his officer corps start fraternizing with the locals.

“The local Gauls and traders affirmed that the Germans were men of a mighty frame and an incredible valour and skill at arms; for they themselves (so they said) at meetings with the Germans had often been unable even to endure their look and the keenness of their eyes. And so great was the panic [among Caesar's officers] and so suddenly did it seize upon all the army, that they were terrified nearly out of their senses. It began first with the tribunes, the prefects and others who had followed Caesar from Rome to court his friendship, without any great experience in warfare.”

And... you know, a lot of these guys are senator's sons, they're here to shine up their CVs, sleep in a tent, rough it a little with some Gallic bushmeats maybe, make some money off the plunder, they think, there's an understanding here Caesar knows their dads, he's not going to turn them into cannon fodder... well these guys start coming to Caesar after hearing about the Germans, and they've got various stories about how, oh you know, bad timing, I need to deal with some business back at the family farm, ah there's a family inheritance matter I need to sort out, gotta get back to Rome, Caesar, you understand these things.

Caesar’s speech to his war council

Caesar sees right through this.

And other guys start saying, you know, really its the soldiers are really concerned, it's not that they are afraid of Ariovistus and the Germans, but there's some concern about the supply lines getting cut off... they're even talking about a mutiny... blah blah blah.

Caesar is very annoyed and he calls a war council and he delivers a long speech to all his officers, even brings in the lower ranking centurions so they can know what he thinks about all this talk.

And he's kind of giving you a lesson in how a leader should encourage people who are really doubting the enterprise they are embarked on.

A first lesson is, learn to recognize fear when you see it, because, probably nobody will openly say, "Hey I'm afraid".

So he begins by reprimanding them, “First and foremost because they thought it was their business to ask or to consider in which direction or with what purpose they were being led.” So first, you might have to shock them out of their fear by shaming them (replace that one negative emotion with another, more productive one).

Then he goes on to explain (I paraphrase) “Ariovistus sought the friendship of the Roman people in the past, I'm sure he'll come around to see reason any moment now” but even if he doesn’t, and we have to fight this out do you doubt the strength of Roman arms? And he reminds them of Gaius Marius' smashing victories over the Cimbri and the Teutones 40 years earlier...(so he FIRST brings in precedents for why they shouldn't be afraid of, yes, the thing they are actually afraid of but not admitting).

(And Gaius Marius here is a very loaded example, Marius was a populist from the previous generation and Caesar has kind of built a career taking on the mantle of Marius... and importantly the constituency of Marius...)

And furthermore Caesar, says—interestingly, this is news to us the readers—that in fact Ariovistus defeated the Aedui not by force and courage... but by subterfuge, lying in wait in the swamps until the Aedui had their guard down. And the Helvetii have beaten the Germans in the past, and you see, we just spanked the Helvetii...so it holds to reason...

Anyway, then, AFTER he's addressed their REAL fear, then he kind of as an afterthought addresses these silly pretences about concern about the supply lines (basically, c'mon, you're talking to Caesar here, logistics is my business, and heres' why we have nothing to worry about, the Sequani and other tribes are bringing us grain etc. etc. so he does address those concerns, and I think that's important because this allows the captains to save a little face).

But so, once he's done with the speech, they are all won over, enthusiastic to start this war, and they say, yes, you know, of course, we were never in the slightest bit afraid, never meant to question your authority sir.

And, well, that's how he settled that matter.

Caesar and Ariovistus’s Parley

Well then, now that the two armies are closer to each other, Ariovistus finally sends some emissaries to say, Ok, we can have a parley now, you know uh now that you've come to me like I (ahem), stipulated.

And long story short, they meet, each with a small mounted detachment. And the two leaders talk on horseback with each other. But—it seems Ariovistus was either trying to buy time with a distraction, or even he was hoping to physically capture Caesar with his guard down as we'll see—before that Ariovistus even dares to say the following in their meeting:

“Unless Caesar departed and withdrew his army from this locality, Ariovistus would regard him, not as a friend, but as an enemy. And if he put Caesar to death (!!), he would gratify many nobles and leaders of the Roman people: this he knew for certain from themselves, by the messengers sent on behalf of all whose favour and friendship he could purchase by Caesar's death. If, however, Caesar departed and resigned to Ariovistus the uninterrupted occupation of Gaul, Ariovistus would recompense him by a great reward, and would, without any exertion or risk on Caesar's part, execute any campaigns he might wish to see carried out.”

Well! (And I like here how Caesar suggests that his political enemies at home who object to his war are corrupt and in the pocket of the enemies of Rome... very deft move, rhetorically) well, after this, Caesar gets busy explaining to Ariovistus that, sorry, this is just not how the Roman People do business and it's not how they treat their allies... backing down on commitments to defend them... and the Romans insisted that the Gauls should be free.

But unfortunately, the meeting actually is broken up prematurely when Ariovistus' knights start hurling stones at Caesar's knights. So both men ride away, nothing is resolved12.

The next day Ariovistus says basically "Hey yesterday that was all a big misunderstanding, lets talk again" But Caesar really doesn't trust him now.

He sends a couple of local Gallic nobles in his place as emissaries, and ...

what do you know, Ariovistus seizes them and puts them in chains.

...and with that, it looks like, it's go time.

The Battle Begins…

Ariovistus moves his camp up to 2 miles away from Caesar's position at Vesontio, he's cutting off supplies to the city.

Caesar marches out, offers an infantry battle. But Ariovistus declines. Strange!

Ariovistus does do some skirmishing with his cavalry though, and listen to Caesar's description of how the Germans do it:

“The kind of fighting in which the Germans had trained themselves was as follows. There were six thousand horsemen, and as many footmen, as swift as they were brave, who had been chosen out of the whole force, one by each horseman for his personal protection. They worked with the horsemen in encounters; on them the horseman would retire, and they would concentrate speedily if any serious difficulty arose; they would form round any trooper who fell from his horse severely wounded; and if it was necessary to advance farther in some direction or to retire more rapidly, their training made them so speedy that they could support themselves by the manes of the horses and keep up their pace.”

Amazing. We're going to see the British do something similar a few episodes from now, and also the Thebans did that at the battle of Mantineia, as we recounted in the life of Agesilaus King of Sparta...

Well anyway, it's all inconclusive for a few days, so Caesar decides to try to provoke Ariovistus a little more, and he moves up and starts building a camp 600 paces from Ariovistus' fort...

Now, Ariovistus responds by sending out all his cavalry, and 16,000 light armed skirmishers to try to harass the Romans (Caesar's got 6 legions I think, so 30,000 men), so the Romans they're digging earthworks and throwing up ramparts, cutting down trees, as the Germans are throwing spears at them... trying to intimidate them.

And here's one of my favorite lines of the book “Caesar did exactly as he had planned” - so he splits up the army, some to build the fort, others to defend the guys building the fort, and he gets it done.

But then, big talking Ariovistus...still keeps his main forces in his camp! What's going on?

Caesar explains:

“By questioning many captives, Caesar found out the reason why Ariovistus did not fight a decisive action.”

I'm going to quote Plutarch here who gives a somewhat more colorful description than Caesar does:

“The spirit of the Germans was blunted by the prophecies of their holy women, who used to foretell the future by observing the eddies in the rivers and by finding signs in the whirlings and splashings of the waters, and now forbade joining battle before a new moon gave its light.”

So he's caught them at a moment where the omens are bad...

Now, if you've come across intelligence that your enemy is holding off from the competition for some, you might say, external reason, well that's a pretty good time to force them to engage you, right when they are most uncomfortable.

And that's exactly what Caesar does.

He draws all of his forces up right before the gates of the enemy camp—and you just know, all of the German generals and lieutenants and the rank and file men are just maddened at the fact that they're looking like cowards refusing to fight.

And so sure enough, Ariovistus finally breaks down and he leads all his men out and lines them up for battle.

Here's what happened next:

“The Germans fenced in their whole battle line with their chariots and wagons arranged behind them in a semicircle. Upon these they set their women, who with tears and outstretched hands entreated the men, as they marched out to fight, not to deliver them into Roman slavery.

This, I suppose, they figured would be motivating , both physically cutting off their escape to the rear with those wagons, and reminding them of the stakes very clearly with the women sitting on them. Going on here:

“Caesar put all of his legates and his quaestor each in command of a legion, that every man might have them as a witness to his valor. He himself took station on the right wing, having noticed that the corresponding division of the enemy was the least steady, and joined battle. Our troops attacked the enemy so fiercely when the signal was given, and the enemy dashed forward so suddenly and swiftly, that there was no time to discharge javelins upon them. So javelins were thrown aside, and it was a sword-fight at close quarters. But the Germans, according to their custom, speedily formed a phalanx, and received the sword-attack. A number of our soldiers were found brave enough to leap on to the phalanx of the enemy, tear the shields from their hands, and deal a wound from above. The left wing of the enemy's line was beaten and put to flight, but their right wing, by sheer weight of numbers, was pressing our line hard. Young Publius Crassus, commanding our cavalry, noticed this, and as he could move more freely than the officers who were occupied in and about the line of battle, he sent the third line in support of our struggling troops.

This restored the battle, and all the enemy turned and ran; and they did not cease in their flight until they reached the Rhine River.”

The Rhine was some 40 or 50 miles away (Caesar says 5 but that seems to be wrong and that's probably due to some medieval copying error).

So you notice there, young Publius Crassus is the man Caesar gives credit for turning the tide in a key moment of the battle. Publius Crassus, the son of Marcus Crassus, Rome’s great financier, the triumvir, Caesar's backer.

Caesar of course knows that Publius' father will be reading these reports.

Mission Accomplished

Well, with that, Caesar chases the Germans all back across the Rhine, those that he's not able to kill or capture before they get there, which he makes it sound like...was actually most of them. Ariovistus himself though manages to get across in a boat and escape to safety, never to terrorize the Gauls again.

Caesar also soon gets reports that other tribes of Germans like the Suebi who had crossed the Rhine further downstream, had wisely decided to go back home to Germany once they heard the news.

And with that, Caesar declares it a job well done, and he sends his troops into winter quarters. Mission accomplished, the Aedui are freed from their oppressors and the Sequani are liberated.

But just one point of curiosity here... Caesar mentions kind of off hand in his narrative that Ariovistus has quite a few Gauls fighting under him as well as Germans. And there's a lost epic poem on this campaign by a guy named Varro of Atax (this is not the more famous Varro, Pompey's friend, different Varro), well, Varro of Atax wrote a poem on the Ariovistus war, but he didn't call it The War with the Germans, or the War with Ariovistus.

He called it Bellum Sequanicum — the war with the Sequani.

Wait, I thought the Sequani were the ones who were pleading for Caesar’s help against Ariovistus their oppressor?

Kind of makes you wonder... maybe there was more to the story, somehow, than what we got.

But hey, aren't all stories that way?

Stay tuned for next time, when we'll go further north and meet the Belgae.

If you enjoyed this, if you love ancient heroes, tell a friend, leave a comment, leave us a good review, it really helps other people find this stuff. And we're on a mission here, after all.

Thanks for listening. Stay Strong, Stay Ancient. This is Alex Petkas, until next time.

This is a guide, from one of the world's all time masters into the inner workings of human psychology, when it is pushed to its limit. When a man faces certain death, what does he do? When you have to make a decision with imperfect information, in the heat of the moment, how do you act? When a proud nation, divided among itself, or a whole confederation, such as the Gauls were... when they are faced with subjugation by outside forces... how do they respond? When the elites of a society see great opportunities on both sides, collaborate with the Romans, or resist... How do they build coalitions and alliances? How do you figure out who you can trust?

In a talk given at Stanford, Don Valentine extolls the power of storytelling: “The art of storytelling is incredibly important. And many—maybe even most of the entrepreneurs who come to talk to us can’t tell the story. Learning to tell a story is incredibly important because that’s how the money works. The money flows as a function of the stories.”

My comments are in square brackets.

Plutarch relates it like this: “We are told that, as he was crossing the Alps and passing by a barbarian village which had very few inhabitants and was a sorry sight, his companions asked with mirth and laughter, ‘Can it be that here too there are ambitious strifes for office, struggles for primacy, and mutual jealousies of powerful men?’ Whereupon Caesar said to them in all seriousness, ‘I would rather be first here than second at Rome’”

It’s an interesting fact that many people in the middle ages thought it was someone else who wrote DBG and not Caesar. But you'd really have to be a clumsy reader to come to that conclusion since he does speak of himself in the 1st person here and there, and also it's pretty explicit at the beginning of book 8.

"Movement of the Peoples"'

“Therefore, before attempting anything in the matter, Caesar ordered Diviciacus to be summoned to his quarters, and, having removed the regular interpreters, conversed with him through the mouth of Gaius Valerius Procillus, a leading man in the Province of Gaul and his own intimate friend, in whom he had the utmost confidence upon all matters. Caesar related the remarks which had been uttered in his presence as concerning Dumnorix at the assembly of the Gauls, and showed what each person had said severally to him upon the same subject. He asked and urged that without offence to the feelings of Diviciacus he might either hear his case himself and pass judgment upon him, or order the Aeduan state so to do.”

Personal presence is important not only for Caesar but for Roman warfare in general, you might say. However Caesar really exhibits these strengths of the Romans to a virtuosic level throughout the text.

Full quote: “forasmuch as in [the year 61] the consulship of Marcus Messalla and Marcus Piso the Senate had decided that the governor of the Province of Gaul should protect, as far as he could do so with advantage to the state, the Aedui and the other friends of the Roman people”

Note too how, in the text, Caesar says explicitly, well, they could have fought back and maybe captured Ariovistus, but Caesar didn’t want a narrative to get out about how he had broken faith. As always note Caesar’s key sensitivity to doing things the right way...

Awesome episode i was captivated by the story telling as always. What was the Egypt podcast teases at the end?

I just finished listening. Great episode 💚 🥃