Caesar almost loses it all, in part 2 of our series on Caesar’s masterwork of psychology, strategy, and propaganda: On the Gallic War (De Bello Gallico).

This is a world-history making story (the conquest of what’s now modern France), told by a world-history making storyteller.

Caesar entered Gaul as a mere politician. He returned 9 years later as a conqueror - and an enemy of the state. He tells how it all happened with his own pen.

In this episode:

-A conspiracy of the powerful, warlike Belgae (Belgian tribes).

-The battle of the Sabis, against the Nervii

-Caesar's terrifying siege tactics

This episode is sponsored by our very generous sponsor, Dr Richard Johnson, an avid Cost of Glory listener. Thanks Richard!

You can listen to the episode here:

Stay Ancient,

Alex

Transcript

“While Caesar was wintering in Cisalpine Gaul... frequent rumours were brought to him, and dispatches also from Titus Labienus informed him, that all the Belgae (whom we have already described as a third of Gaul) were conspiring against the People of Rome and giving hostages each to the other.”

Cum esset Caesar in citeriore Gallia... crebri ad eum rumores adferebantur litterisque item Labieni certior fiebat omnes Belgas, quam tertiam esse Galliae partem dixeramus, contra populum Romanum coniurare obsidesque inter se dare.

— Caesar, Gallic War Book II

You know, when you start winning, and levelling up, other people are going to take notice. And want to get rid of you.

This is the story of Caesar's second year campaigning in Gaul. And we are going to get to see how Caesar and his men act when they are really on the EDGE.

And of course, this is all straight from the pen of the man himself.

I'm Alex Petkas and you are listening to the Cost of Glory, where it is our mission to retell the lives, deeds, and characters, of the greatest Greek and Roman heroes.

This is part 2 of 8 of the Gallic Campaigns of Julius Caesar.

Cost of Glory is an Infinite Media Collaboration.

If you love great heroes and want to help us reach more people with these LITERALLY LIFE CHANGING stories, and/or if have a product or service or company you think might be of interest to CoG listeners, reach out to me at alex@ancientlifecoach.com.

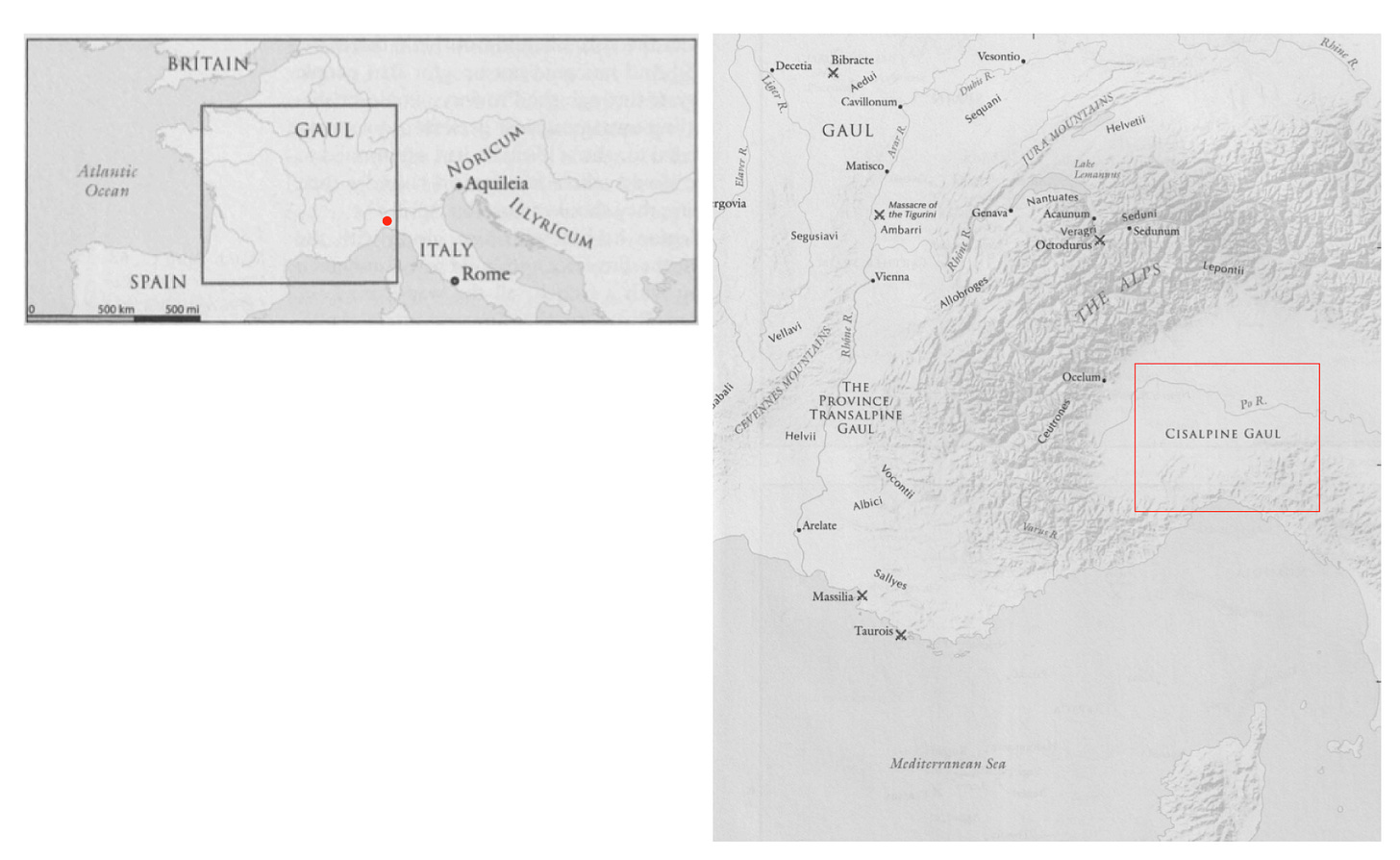

Now before we get to the war part of this book, one of the things that I find so amazing about Caesar's conquest of Gaul is how many OTHER THINGS he was ALSO DOING. We'll get to his literary activities later on... but you may have noticed with that opening quote, Caesar said, he's wintering in Cisalpine Gaul.

Cisalpine Gaul is really northern Italy north of the Po river, the Padanus as the Romans called it.

Caesar holds Court

And here's how Plutarch describes what he does there (again the year is 57, early in the year, still winter):

“Caesar left his forces among the Sequani to spend the winter, while he himself, desirous of giving attention to matters at Rome, came down to Gaul along the Po, which was a part of the province assigned to him (that's Cisapline Gaul)... Here Caesar fixed his quarters and carried on his political schemes. Many came to see him, and he gave each one what he wanted, and sent all away in actual possession of some of his favours and hoping for more. And during all the rest of the time of his campaigns in Gaul, unnoticed by Pompey, he was alternately subduing the enemy with the arms of the citizens, or capturing and subduing the citizens with the money which he got from the enemy.”

— Plutarch, Life of Caesar (#20)

So a provincial governor's duty will be holding the assizes, which is like a traveling court of appeals, [where] the governor has to hear all of these cases, property disputes, tax arrears, lots of minutiae. But he's also building up a kind of power base and political network while he's doing that. And also he's doing this work for the province of Illyria and Transalpine Gaul at the same time, I mean, it's an incredible administrative workload he's got to supervise (even if he can delegate a lot of it).

Most governors would be satisfied just doing all of that for one province, but Caesar is splitting his time doing all this and meanwhile, executing on his mission of becoming one of History's greatest conquerors (to be fair, he's chunking his time at different times of the year, but I still think this is really impressive... the energy of the man).

Alright so... to the new war brewing with the Belgae.

The Belgae, are in and around modern Belgium. They're sort of distant neighbors to the Sequani and the Aedui that we were dealing with in the last chapter. We'll get to the Belgae and who they are in a second. But here's Caesar explaining what's going on:

“The causes of their conspiracy, it was said, were as follows. In the first place, [The Belgae] feared that when all Gaul was pacified they might themselves be brought face to face with a Roman army; in the second, they were being stirred up by certain of the Gauls, who had either been unwilling that the Germans should stay longer in Gaul, and were now no less distressed that a Roman army should winter and establish itself in Gaul, or who for sheer fickleness and inconstancy were set upon a change of rule1... and this they could not so readily effect under our empire.”

So Caesar noted at the end of the last book that he actually left his legions in Gaul when he went back to Italy to do his governor stuff. He's talking about the territory of the Aedui and the Sequani, that's pretty FAR outside the Roman province of Transalpine Gaul/east central France.

And you could argue, this was reasonable, right? It's not customary for a Roman general to do this, especially in a region that's not the province, but it's not not done either—and you gotta wonder, did Caesar know this?—well it's also kind of a provocation, you could argue. It sends a message to the nearby tribes, who aren't pacified. Hey, the Romans may be here to stay.

So the Belgae decide to take some preemptive action and start preparing for war. Not clear at this point in the narrative whether they intend to attack, or whether they just want to be ready to defend...but they're taking major actions, and Caesar finds out about this.

One of the Roman commanders who's forwarding this intelligence to him by the way is Titus Labienus, that's basically his second in Command—Labienus plays an important role later in this book. You might remember him from the Life of Pompey, he's a big player in the civil wars actually, he defects famously from Caesar...but let's stay on course here.

The Belgae get ready…and Caesar responds

Now, so the Belgae are all convening their leaders and gathering, it's a big tribal confederacy of multiple tribes, that we'll meet shortly. And Caesar takes SWIFT ACTION: he raises two new legions in Cisalpine Gaul, and gets to the borders of the Belgae real fast in the spring—kind of shocks them.

When he gets there, some emissaries from one of the tribes of the Belgae approach him. These are the Remi.

The Remi live in what's now northern France, in fact their capital was the modern city of Reims. It's about 2 hours by car north-east of Paris, in the direction of Belgium.

And these Remi say, hey, we don't want to have anything to do with this conspiracy, we want to help you Romans out, and Caesar accepts.

Well the Remi report that the Belgae are even inviting the Germans who live across the Rhine to ally with them against the Romans, so you know, it’s serious.

Here's how Caesar describes the Belgae:

“Caesar asked [the Remi] what states were under arms, what was their size and their war‑strength. He discovered that most of the Belgae were of German origin, and had been brought over the Rhine a long while ago, and had settled in their present abode by reason of the fruitfulness of the soil, having driven out the Gauls who inhabited the district. [this is an ancient origin story the Belgae tell about themselves, they're actually Gauls and they speak a Celtic language like the other Gauls, but you know, claiming descent from the Germans makes them seem tougher; going on here]. The Belgae, they said [the Remi], were the only nation who, when all Gaul was harassed in the last generation, had prevented the Teutones and Cimbri from entering within their borders; and for this cause they relied on the remembrance of those events to assume great authority and great airs in military matters.”

Tough guys these Belgae. Here are some of the tribes of the Belgae that are taking arms according to Caesar:

A lot of these tribes have given their names to modern places in France and Belgium:

The Bellovaci - hence the city of Beauvais, about an hour north of Paris; they've got 100k men at arms!

The Suessiones, whence the city of Soissons, between Beauvais and Reims [Napoleon in his commentaries just refers to these various tribes by their modern French names, like “The men of Soissons, The men of Beauvais”]. They've got 50k fighters...

The Nervii, another 50k, no significant modern place names but Caesar notes these are among the most warlike of them all (more on them shortly), the Nervii live in what's now Belgium proper...

Then there are the Atrebates, the "Men of Artois" as Napoleon puts it (that's Belgium proper again), 15k

…and the Ambiani, the men of Amiens... another 10k, and several more tribes, and notably, 40k various German tribes from across the Rhine too.

So, it's a pretty big coalition from the sound of it. Caesar's got 8 legions now, something like 50k men.

And it seems that Caesar here kind of initiates hostilities, but kind of doesn't. Listen to this:

“Caesar made a powerful and a personal appeal [the wording is important] to Diviciacus the Aeduan [this is his friend, remember him from the last episode], showing [Diviciacus] how important an advantage it was for the Roman state, and for the welfare of both parties, to keep the contingents of the enemy apart, so as to avoid the necessity of fighting at one time against so large a host. This could be done if the Aedui led their own forces into the borders of the Bellovaci and began to lay waste their lands.”

What he does is, he gets Diviciacus and the Aedui to attack the Bellovaci's farmlands, and harass them, they're a little further afield from the rest of the Belgae... and the wording there is key: he's not commanding the Aedui, just saying, hey “It would be a good idea and in our mutual interests” - so, Caesar's got some deniability there.

The Aedui kind of start the fight with this huge Belgae coalition.

Now, what do you know, the Belgae respond by attacking a city of the Remi, who are now, Roman allies...

So... Caesar's got to respond, right?

And this is really clever on his part. He sees, there's going to be trouble with the Belgae one way or another... let's do it on OUR TERMS... and so he kind of provokes them into taking a course that would make it justifiable for the Roman commander here to intervene.

So that's a pretty good way to start a fight, if you see it coming, find a way to control how it will start, ideally in a way that gives you some deniability, to say, hey, you're just defending yourself or your interests.

So Caesar of course intervenes.. I'll skip the siege the Belgae launch on the town of the Remi, the Barbarians use the tortoise shell formation, you know, shields over heads, maybe it's something they learned from the Romans... and they attack the walls of this town of the Remi, and it gets pretty bad for the Remi, but Caesar manages to relieve them just in time.

And what ends up happening is, the Belgae decide to retreat... not least, Caesar notes, because the Bellovaci (these are the guys with the largest contribution, 100k soldiers), are really getting anxious about all their farms being burned by Diviciacus the Aeduan.

In the process though, before this, Caesar notes, how HUGE the Belgae army is, their camp, as he was able to discern from the smoke from the campfires...was 8 miles across...amazing. It was some 300k men, according to his report. Wow.

So, things seem to be going well at first.

The Bellovaci head home, the other Belgae retreat to regroup, and in this mass people movement, there's a lot of chaos and there's some river crossing, and and Caesar is able to attack and destroy large sections of the Belgian armies.

A Roman crackdown

Then Caesar goes and attacks Noviodunum, which is Soissons, the capital city of the Suessiones. He can't take it by a quick storm, so he gets the Roman engineering machine operating. Here's Caesar on how that went:

“[Caesar] entrenched his camp, therefore, and began to move up mantlets and to make ready the appliances needed for assault. [Mantlets here, could also be translated as "roofed sheds" - these so these are portable shelters that the Romans build as step 1 of their devastating siege machine... the Latin is "Vinea" - which means, "vine" - I think the idea is that the Romans build these sheds that gradually extend like tendrils from their camp towards the walls of your city... so they can build their war ramps and dig tunnels to undermine your walls, and it must have a pretty terrifying effect... especially when you see them building the siege towers they're getting ready to roll up and capture your town. Here's how the Suessiones react:] ... When the mantlets were speedily moved up to the town, a ramp cast up, and towers constructed, the Gauls were disturbed by the size of the siege-works, which they had not seen or heard of before, and by the rapidity of the Romans, to send deputies to Caesar to treat of surrender; and upon the Remi interceding for their salvation, they obtained their request.”

The Landmark edition commentator Kurt Raaflaub puts it well here: “As often, it was the speed and efficiency of the Roman preparations and the visual impression created by the siege works, as well as the way the soldiers went about their business with grim and professional determination, that demoralized the defenders.”

So, all is going well...just another routine Roman crackdown here...

And Caesar gets to do a solid for his loyal man Diviciacus of the Aedui, listen to this (and Caesar drops a little breadcrumb here for something he's got in mind for LATER...see if you can spot it):

“Diviciacus, who had returned to Caesar after the Belgae had withdrawn, and had dismissed the forces of the Aedui, now spoke on behalf of the Bellovaci, as follows: "The Bellovaci have always enjoyed the protection and friendship of the Aeduan state. They have been incited by their chiefs who declared that the Aedui have been reduced to slavery by Caesar and are suffering from every form of indignity and insult, both to revolt from the Aedui and to make war on the Roman people. The leaders of the plot, perceiving how great a disaster they have brought on the state, have fled to Britain. Not only the Bellovaci, but the Aedui also on their behalf, beseech you to show your customary mercy and kindness towards them. By so doing you will enlarge the authority of the Aedui among all the Belgae, for it is by the succours and the resources of Aedui that they have been used to sustain the burden of any wars that may have occurred.”

So... did you catch it? These bad leaders fled to Britain! that exotic island Roman standards have never marched: a possible hotbed of discontent? File that one away.

So, Diviciacus' proposal is, basically, the Romans spare the Bellovaci and forgive them for their part in this conspiracy, and Diviciacus and the Aedui basically get to pick their new rulers from among them, loyal men.

And Caesar loves this idea, reward your loyal allies, and the Aedui get to have the powerful Bellovaci as a sort of client and ally.

I think all this just points out to you how, a loose federation of independent states has a big disadvantage against a great power. This is something Alexander Hamilton was really insistent upon preventing in the early days of the United States, a lot of people wanted a weak federal government, more independence for the 13 colonies... but Hamilton wanted make a strong central government, precisely so that some Caesar (or England or France or Spain as the case may be) couldn't come in and play them off each other.

And with that, Caesar breathes a sigh of satisfaction.

The refusal of the Nervii

So now, various tribes of the Belgae and other Gauls are sending emissaries, suing for peace with the Romans. But here's where it starts to get interesting.

One tribe in particular, the Nervii, refuse. Here's Caesar on the Nervii:

“On the borders of the Ambiani [the "men of Amiens"] lived the Nervii, and when Caesar inquired as to the nature and character of these men, he discovered as follows. Traders had no means of access to them, for they allowed no wine nor any of the other appurtenances of luxury to be imported, because they supposed that their spirit was like to be enfeebled and their courage relaxed thereby. Fierce men they were, of a great courage, denouncing and accusing the rest of the Belgae for surrendering to Rome and casting away the courage of their forefathers. For themselves they affirmed that they would send no deputies and accept no terms of peace.”

Remember they're already at war, so anything goes now more or less. And the Nervii have brought along some of their neighbors into resisting too. So Caesar gets to work.

He marches into the territory of the Nervii, and he sends some scouts ahead to find a good place for a camp, and heads toward it.

Now... he's got in his army a number of the Belgae who had surrendered and other Gauls marching with him. And some of these, it turns out, are still quietly rooting for the Belgae to defeat the Romans, and they send word to the Nervii secretly. They say, Caesar's column is spread out like a long, weak string, he's got baggage trains separating all the legions, it would be really easy to take him by surprise here.

So the Nervii decide to set up an ambush (note how Caesar sets that up nicely, builds some suspense, helps you understand their motivations and their probable strategy).

Here's Caesar with more on what the Nervii are getting ready with:

“The plan proposed by those who brought the information was further assisted by an ancient practice of the Nervii. Having no strength in cavalry (for even to this day they care nothing for cavalry, , but all their power lies in the strength of their infantry), in order more easily to hamper the cavalry of their neighbors, whenever these make a raid on them, they cut into young saplings and bent them over [so they're sort of terraforming here, bending over these young saplings that grow sideways], and thus by the thick horizontal growth of boughs, and by intertwining with them brambles and thorns, they contrive that these wall-like hedges serve for them as though fortifications... which not only can not be penetrated, but not even seen through.”

So you've got to imagine the Nervii sneaking around behind these impenetrable hedge walls, scheming, as the Romans are marching through unawares...

And they wait til Caesar is setting up his camp before they strike. But first Caesar's going to describe the topography of what turns out to be an epic battle they're about to fight:

“The character of the ground selected by our officers for the camp was as follows. There was a hill, inclining with uniform slope from its top [down] to the river Sambre [this is the Sabis in Latin]. From the [opposite] river-side there rose another hill of like slope, over against and confronting the other, open land for about two hundred paces at its base, then wooded in its upper half, so that it could not easily be seen through from outside. Within those woods the enemy kept themselves in hiding. On the open ground along [that opposite river bank] a few enemy cavalry posts were to be seen. The depth of the river was about three feet.”

So Caesar sees a few enemy cavalry across the river from where he wants to make his camp [I guess this must be some of the Allies of the Nervii, who don't completely ignore the art of horsemanship], and so he sends his cavalry ahead across the shallow river to chase them away while he's building a fort on the hill. And the enemy cavalry engage for a while, then retreat into the forest, the Roman cavalry keep strict discipline, they don't follow into the forest... and the enemy come in and fade out, and this goes on for a while.

And then... there's a key twist here:

“However, the arrangement and order of Caesar's column was different from the report given by the Belgae to the Nervii. For, as he was approaching the enemy, Caesar, according to his custom, was moving with six legions in light field order; after them he had placed the baggage of the whole army; then the two legions which had been last enrolled brought up the rear of the whole column and formed the baggage-guard.”

In other words, Caesar was not marching with his army all strung out and baggage train stuck between legions, like vegetables on a shish kabob...but rather he had 6 legions, his stronger ones, all in front, basically ready to fight, then all the baggage, and then the new recruits at the back defending the baggage train.

If he hadn't done this... that is, if he hadn't been basically ready to fight right off the march... well, let's just say world history might have gone very differently.

So the Romans, basically, hyper organized as usual, straightaway once they get to the hill, start making their camp, measuring out the grounds, chopping down trees, digging ditches...

The Nervii Ambush

And right at this moment, the Nervii strike.

They sweep out of the forest on the other side of the river, tens of thousands of men, completely overwhelm the Roman cavalry and chase them across the river, and start sprinting up the hill to the Romans, who have already shifted out of soldier mode and into construction company mode.

And here's Caesar on what happened next, and his whole description here gives you a lot of vivid details of how the Romans usually got ready for battle...and couldn't quite do so on this occasion:

“Caesar had to do everything at once: he had to raise the flag to give the signal to call soldiers to to arms; to have the trumpet blow the battle signal; to recall the troops from their entrenching; to bring in the men who had gone somewhat farther afield in search of materials for the ramp; he had the line to form; the troops to harangue; the signal to give. A great part of these duties was prevented by the shortness of the time and the advance of the enemy [so in other words, he's not actually able to do all of these things]. The stress of the moment was relieved by two things: the knowledge and experience of the troops — for their training in previous battles enabled them to assess for themselves what was proper to be done as readily as others could have shown them — and the fact that Caesar had forbidden the several lieutenant-generals [the legats] to leave the entrenching and their proper legions until the camp was fortified. These generals, seeing the nearness and the speed of the enemy, waited no more for a command from Caesar, but took on their own account what steps seemed to them proper.”

Ok so you've got masses of very motivated, tall men, coming in hot, everybody in the Roman side is starting to get very nervous, but the soldiers and officers hold their ground and brace for the attack.

Here's what Caesar himself does:

“Caesar gave the necessary commands, and then ran down to whatever unit happened to be the closest, and came to the Tenth Legion [ah, the trusty 10th!]. His harangue to the troops was no more than a charge to bear in mind their traditional valour, not to panic, and to bravely withstand the onslaught of the enemy; then, as the enemy were no farther off than the range of a missile, he gave the signal to engage.”

Now what he says to the men is obvious, right, this is what you know you should do. Be brave, don't panic. But it really matters that the commander says this. And the words he uses here are really well chosen: remember your “Traditional Valor”.

The Latin here is pristina virtus: that could also be translated as "ancient manliness" (virtus is virtue but also battle prowess, also, really, the best Latin translation of manliness...)

The connotations of Pristina there, pristine, evoke the ancestral age of Roman Republican greatness, the virtue of past generations who defeated Pyrrhus, Hannibal, the Cimbri, Teutones, and other great enemies.

He's reminding them, telling them, with those two words, who they are - appealing to their identity, a very powerful motivator.

So, they're on this hill as the Nervii and allies attack, and Caesar says, they don't have time to form up proper battle formation, but each legion is more or less clumped together and they are arranged in a kind of semicircle around the hill, trying to defend only the very rudimentary beginnings of a proper camp site.

Caesar runs from the 10th on one side to a legion on the other side, gives them the same words, trying to float above the formation and see what's needed where.

And he adds:

“The time was so short, the temper of the enemy so ready for conflict, that there was no space not only to attach their crests and insignia in their places, but even to put on helmets and draw covers from shields. In whichever direction each man chanced to come in from the entrenching, whatever standard each first caught sight of, by that he stood, to lose no fighting time in seeking out his proper company.”

So these men are basically, fighting up with whatever group they happen to be standing, and the crests and insignia and shields he mentions, these are some of the things that distinguish say, a centurion from a private, a tribune from a centurion, a legate from a tribune.

There's a sense of, we're all in this catastrophic mess together... Think of the kind of whole-army camaraderie that this would build for your men—IF that is, you manage to survive.

As Caesar notes, given the enormous difficulties, it was only to be expected that the fortunes and outcomes on different parts of the battlefield would vary a great deal.

The 9th and the 10th hurl their spears and drive down into the Atrebates (the "men of Artois...") and they manage to drive them all the way down and back across the river, Labienus is leading these veterans. The men of Artois regroup, charge back, but Labienus and the Romans hold them off.

On another side of the hill, the 8th and the 11th drive off the Viromandui - the men of Vermandois.

But elsewhere…it gets bad.

The gradual movement of the battle, driving away Belgians from the hill and pursuing them leaves a big gap in the middle of the lines, and it exposes the camp. The Nervii themselves, with their great commander Boduognatus leading the charge, force into the camp in a dense column.

And they overrun it! The Nervii have taken the top of the hill! Then they wheel around and start pressing on the exposed flank of the 7th and the 12th!

Meanwhile, the camp servants and slaves see the camp overrun, and they think, it's over and many of them panic and run. Then some of Caesar's other allied cavalry ride up (and all this time by the way, his marching column line of 50,000 soldiers and their equipment is still gradually trickling in. The Belgae chose the exact moment when they saw the baggage train start to arrive to attack...)

So here's what some of his allies do:

“All these events alarmed certain horsemen of the Treveri, whose reputation for valour among the Gauls is unique. Their state had sent them to Caesar as auxiliaries; but when they saw our camp filled with the host of the enemy, our legions hard pressed and almost surrounded in their grip, the camp attendants, horsemen, slingers, Numidians, sundered, scattered, and fleeing in all directions, in despair of our fortunes they made haste for home, and reported to their state that the Romans were repulsed and overcome, and that the enemy had taken possession of their camp and baggage-train.”

They think it's over. But as long as Caesar's alive, it's never over.

Here's what Caesar does now that the Nervii have taken the camp and are pressing his right wing:

“Caesar started for the right wing. There he beheld his troops hard driven, and the men of the Twelfth Legion, with their standards collected in one place, so closely packed that they hampered each other for fighting. All the centurions of the fourth cohort had been slain, and the standard-bearer likewise, and the standard was lost; almost all the centurions of the other cohorts were either wounded or killed, among them the chief centurion, Publius Sextius Baculus, bravest of the brave, who was overcome by many grievous wounds, so that he could no longer hold himself upright.”

Centurions by the way here are the sergeants who have worked themselves up from the ranks by their skill and valor, to lead a century, of 60 men. There are 2 centurions in a maniple, 3 maniples in a cohort, and 10 cohorts in a legion. These are very heavy casualties Caesar is noting here among his NCOs... but as Adrian Goldsworthy notes that “Centurions led from the front and suffered disproportionately high casualties as a result” in Roman battles2.

So how does Caesar inspire the loyalty in these kind of brave men to stand their ground and fight? Well, imagine if you are Publius Sextius Baculus, bravest of the brave... and Caesar records your name in his commentaries for posterity, and for the cheering crowds in the Forum to hear... Imagine getting a shout out like that.

And then, even more importantly:

“The rest of the men were growing exhausted, and some of the rearmost ranks, abandoning the fight, were retiring to avoid the missiles; the enemy were continually forcing upwards from the lower ground in the front, and were also pressing hard on either flank. The condition of affairs, as Caesar saw, was on a knife's edge, and there was no support that could be sent up. Taking therefore a shield from a soldier of the rearmost ranks, as he himself had arrived without a shield, Caesar went forward up to the front line, and, calling on the centurions by name [because he's taken the time to learn them all, right?], and cheering on the rank and file, he bade them advance and spread out the ranks of their units, that they might use their swords more easily. His coming brought hope to the troops and renewed their spirit; each man of his own accord, in sight of the commander-in‑chief, desperate as his own case might be, was motivated to do his utmost. So the onslaught of the enemy was slowed down a little.”

This is what nobility looks like in action. It's practically the definition of aristocracy, right there.

Plutarch notes that in all probability, the entire army of the Romans would have been destroyed had Caesar not done what he did there. It would have been another Battle of Cannae, or Arausio, or Teutoburg Forest.

Reinforcements arrive…and Caesar wins

Now then, he's done his job there, Caesar moves on.

“Perceiving that the Seventh Legion, which had formed up near at hand, was also hard pressed by the enemy, Caesar instructed the tribunes to close the legions gradually together, and then, wheeling, around, to advance against the enemy. This was done; and as one soldier supported another, and now they did not fear that their rear would be surrounded by the enemy, they began to resist more boldly and to fight more bravely. Meanwhile the soldiers of the two legions which had acted as baggage-guard at the rear of the column [his reserves] heard news of the action. Pressing on with all speed, they became visible to the enemy on the crest of the hill; and Titus Labienus, having taken possession of the enemy's camp, and observed from the higher ground what was going on in our own camp, sent the Tenth Legion to support our troops [he sends them back across the river]. When these learnt from the flight of cavalry and sutlers the state of affairs, and the grave danger in which the camp, the legions, and the commander-in‑chief were placed, they spared not a tittle of their speed.”

So Caesar's held the lines long enough for reinforcements to come, for the situation to change. SUCH an important lesson. So much of winning is just surviving long enough.

Here's what happens next:

“The arrival of these men wrought a great change in the situation. Even such of our troops as had fallen under stress of wounds propped themselves up on their shields and renewed the fight; then the camp attendants, seeing the panic of the enemy, met their armed assault even without arms [these are the slaves and servants, joining the fray with pots and pans and tent poles and shovels]; finally, the cavalry [the cavalry, you'll recall, who was overrun across the river on the enemy's sudden surprise attack], to obliterate by valour the disgrace of their [earlier] flight, fought at every point in the effort to surpass the legionaries.”

But it's not going to be easy, listen to this:

“The enemy, however, even when their hope of safety was at an end, displayed prodigious courage. When their front ranks had fallen, the next stood on the prostrate forms and fought from atop of them; when these were cast down, and the corpses were piled up in heaps, the survivors, standing as it were upon a mound, hurled darts down on our troops, or caught and returned our pikes. Not without reason, therefore, was it to be concluded that these were men of a great courage, who had dared to cross a very broad river, to climb very high banks, and to press up over most unfavourable ground. These were tasks of the utmost difficulty, but greatness of courage had made them seem easy.”

Finally, the Belgae army is exhausted, and annihilated, and Caesar is victorious. Here's the aftermath:

“This engagement brought the name and nation of the Nervii almost to utter destruction. Upon report of the battle, the older men, who... had been gathered with the women and children in the creeks and marshes [a number of miles away] supposed that there was nothing to hinder the victors, nothing to save the vanquished; and so, with the consent of all the survivors, they sent deputies to Caesar and surrendered to him. In relating the disaster which had come upon their state, they declared that from six hundred senators they had been reduced to three, and from sixty thousand to barely five hundred that could bear arms. To show himself merciful towards their pitiful suppliance, Caesar was most careful for their preservation; he bade them keep their own territory and towns, and commanded their neighbours to restrain themselves and their dependents from outrage and injury.”

Caesar gets a chance here to exercise his famous clementia...his clemency.

And... I think we should pour out a libation in their honor, the bravest of the Belgae, but you know, before you mourn the destruction of the Nervii, don't worry, they'll be back in force for more mischief in later books. Caesar may be exaggerating the extent of their destruction.

So that is the story of when Caesar, on a razor's edge, almost lost it all, but saved the situation by his personal bravery.

Coda, and the Aduatuci

But there's one final episode before this book closes that's worth mentioning.

There's another tribe of Belgae that were on their way to join with the Nervii when they heard the news of their destruction at the Battle of the Sabis River (that's what it came to be called):

The Aduatuci.

These retreat to a very well fortified stronghold, and refuse to surrender.

And here's what happens when Caesar and his legions arrive to subdue them:

“And now, upon the first arrival of our army, The Aduatuci made frequent sallies from the stronghold, and engaged in petty encounters with our troops. Afterwards, when they had around them a fortified rampart twelve feet high, with forts at close interval, they kept within the town. When our mantlets had been pushed up (these are the portable sheds, the vines, remember) and a ramp constructed, and they saw a tower set up in the distance, at first they laughed at us from the wall, and loudly railed upon us for erecting so great an engine at so great a distance. By what handiwork, said they, by what strength could men, especially of so puny a stature, hope to set so heavy a tower on the wall? (for, as a rule, our stature, short by comparison with their own huge physique, is despised by the Gauls)”

So they are thumbing their noses "You don't scare us you Roman pig dogs"...but... then they see the tower moving towards them...slowly, inexorably, up the ramp.

They send out some emissaries and offer to turn over the town, but they plead with him to let them keep their weapons, you see, not so they can resist the Romans, you know, of course, but their neighbors are always warring with them (you have to remember, with these Gauls, taking all their weapons is like taking away all their golf clubs — it's a way of life; this is what these people do).

Caesar says, no way, gotta give up those weapons.

So they say fine and they go back, and soon the Aduatuci start hurling their weapons over the wall into the ditch below... and Caesar says it fills up the trench and the pile of arms nearly reaches the wall of the city. Wow. And they let Caesar's guards into the city.

It turns out however, that that was only about a third of their weapons, and they kept the rest concealed. And that night, Caesar has his guards retreat from the city to avoid any mischief, well, the Aduatuci break out and try to storm and set fire to Caesar's camp. But the Romans defeat them utterly. And…well, you know, once you break faith with the Romans, you lose all privileges.

Caesar captures the city, and he sells off all the living souls to the slave merchants that follow along with the camp (one of these sad grim realities of war).

Meanwhile Caesar reports that he's received word from young Publius Crassus who was sent out on a mission earlier in the book, and Crassus reports that with a mere one legion, he has gone and received the submission of all the Gallic tribes along the Atlantic. This is the Publius Crassus, again, the son of the Richest Man in Rome and Power Broker and Caesar's Financier Marcus Licinius Crassus. Publius, the brilliant young lieutenant who turned the tide of battle against Ariovistus. Also the one who years later fell in the great disaster at the Battle of Carrhae in Mesopotamia, as we've told in episode 3 of the Life of Crassus.

Well then, as Caesar says, with “All gaul pacified by these successes”, news spreads around and emissaries from other tribes come and offer him pledges of fealty.

Caesar stations his troops in Winter Quarters... IN GAUL, once again, of course. And heads back to Illyricum to do his governor business in the off-season.

And, very noteworthy here, he closes the book with the following report:

“For these accomplishments, based on a report of Caesar, a public thanksgiving of fifteen days was decreed [at Rome], which had never been done for anyone before.”

This public celebration was of course declared by the Roman Senate. Pompey got a mere 10 day thanksgiving after defeating Mithridates.

This is a point of pride, for Caesar. But it also meant that the Senate was in effect ratifying all of his legally dubious actions in Gaul over the past 2 years. So it's a huge political win on the homefront.

But as we know, judging by the fact that we have 6 more books left in the commentaries...All of Gaul was far from pacified.

But more on that, next time.

If you enjoyed this, please tell a friend, leave a comment, leave us a good review, it really helps people find this material and get inspired to live their best ancient life now.

Thanks for listening. Stay Strong, Stay Ancient. This is Alex Petkas, until next time.

I didn’t include the phrase (which was part of the original line): “in certain cases, too, the agitation was due to the fact that in Gaul the more powerful chiefs, and such as had the means to hire men, commonly endeavoured to make themselves kings”. This is possible a later insertion.

Goldsworthy on centurions: "Caesar carefully cultivated them, learning their names, in much the same way that he and other senators took the trouble to greet passers-by by name in the Forum. The bond that was created between the proconsul and these officers was intensely personal. Centurions led from the front and suffered disproportionately high casualties as a result." (Caesar: Life of a Colossus, p 234)

Great episode, I enjoyed it! Looking forward to part #3! 💚 🥃